Welcome Back, Western Flycatcher and American Goshawk

September 27, 2023From the Autumn 2023 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

The American Ornithological Society released its 2023 North American bird checklist supplement in July, and the update to the ornithological community’s official list of recognized species has a decidedly retro feel to it.

A headliner of the new update is the splitting of Northern Goshawk into two species—American Goshawk and Eurasian Goshawk. The split follows the recommendation of George Sangster, a researcher at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands, who documented genetic and vocal differences among goshawks in North America and Eurasia. “American Goshawk” represents the return of a species name that was previously recognized from the 1880s to the mid-20th century.

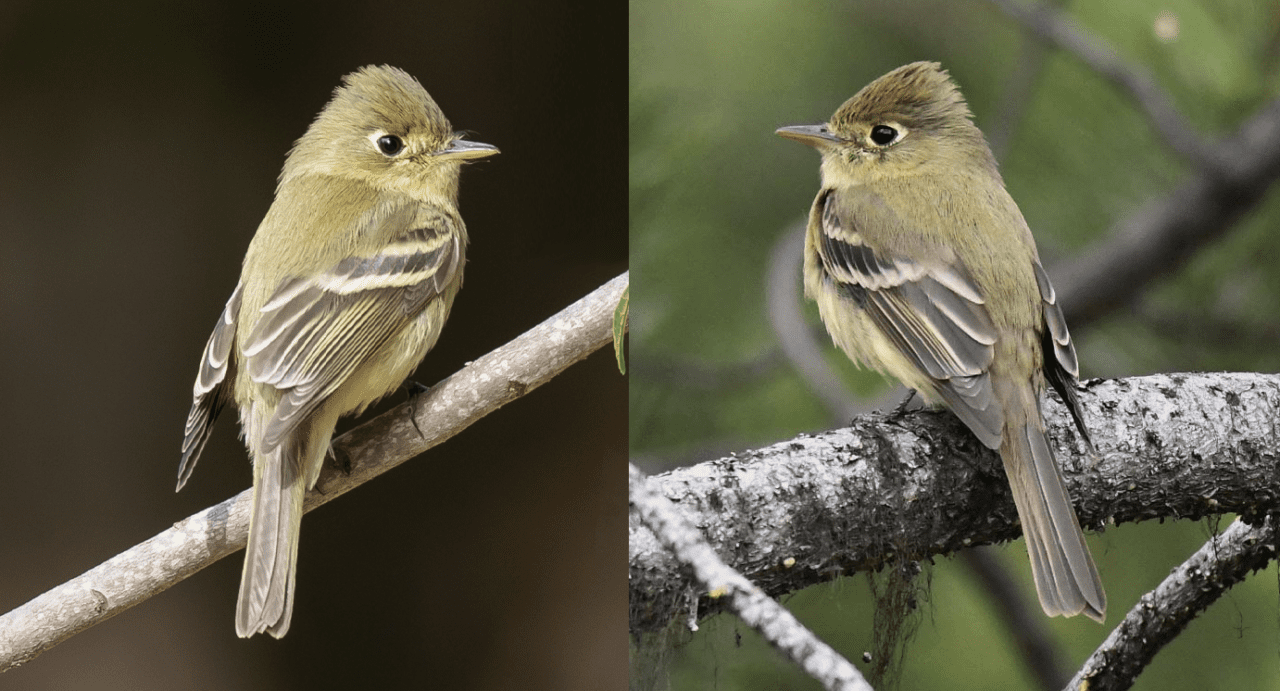

The latest checklist supplement also turned back the clock on a yellow-olive Empidonax flycatcher, by lumping Pacific-slope Flycatcher and Cordilleran Flycatcher into a single species called Western Flycatcher. The lumping reverses an AOS North American Checklist Committee decision in 1989 that split the Western Flycatcher.

Colorado-based researcher W. Alexander Hopping (a recent Cornell University graduate) and Ethan Linck, assistant professor at Montana State University, conducted the research that made the case for lumping the Western Flycatcher. They found that where both forms occur in southwestern Canada and the northwestern U.S., there are no consistent physical, vocal, or genetic differences.

Shawn Billerman, a Cornell Lab of Ornithology scientist who studies the process of speciation among birds, is a member of the AOS checklist committee that reviewed the flycatcher lumping proposal. He says that in the expansive area where the former Pacific-slope and Cordilleran Flycatchers overlap, “it’s impossible to tell them apart because the birds there are truly intermediate between the forms. You only have hybrids”—which means there is evidence of extensive interbreeding.

Several Caribbean bird species splits round out this year’s checklist supplement highlights, including newly recognized endemics for Cuba (Cuban Nightjar, Cuban Palm-Crow, and Cuban Bullfinch), Hispaniola (Hispaniolan Nightjar, Hispaniolan Palm-Crow, and Hispaniolan Euphonia), Puerto Rico (Puerto Rican Euphonia), and Grand Cayman (Grand Cayman Bullfinch).

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library