Bergmann’s Rule May Hint at Adapability of Song Sparrows

April 1, 2024From the Spring 2024 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

North American Song Sparrows may have some resilience to climate change built into their genes, thanks to a remarkable adaptation that accounts for the stunning range of body sizes found throughout the bird’s westernmost range.

That adaptation was the focus of a study, published November 7 in the journal Nature Communications, that offers support for Bergmann’s Rule—a pattern in zoology where, broadly speaking, natural selection in colder climates leads to larger-bodied organisms, while warmer climates lead to smaller bodies. Among organisms that regulate their own heat, larger bodies are more efficient at retaining heat, while smaller bodies allow an organism to stay cooler.

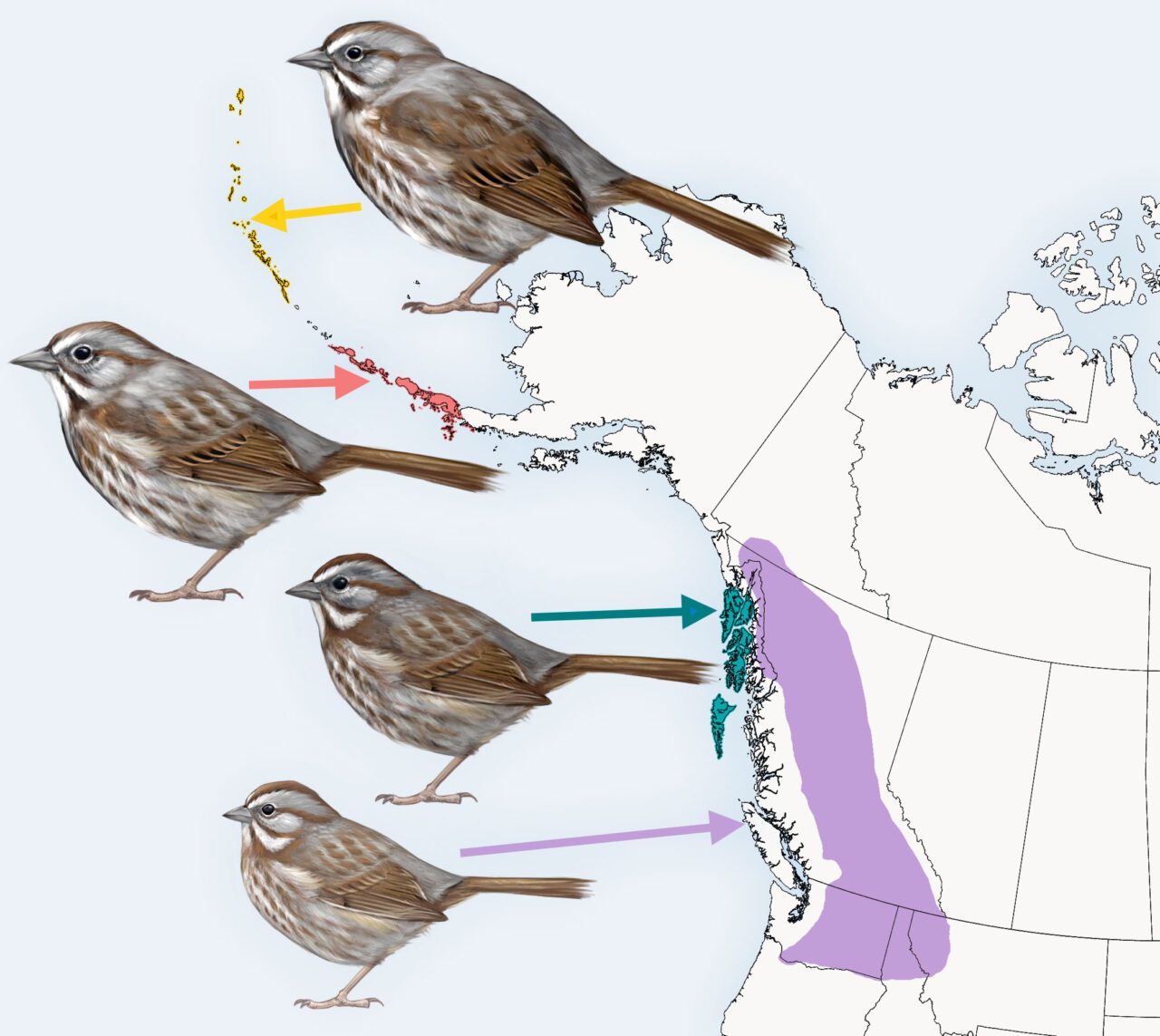

The study found that Song Sparrows that live year-round on Alaska’s Aleutian Islands can be up to three times larger than their cousins near San Francisco Bay.

“The size difference among Song Sparrows is wild to even think about,” says coauthor Jennifer Walsh, a research associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “Our results show that Song Sparrows have substantial capacity for adapting to local environmental change, and the genetic mechanisms underlying those changes are quite clear.”

Walsh and her collaborators conducted whole-genome sequencing and compared 79 genomes from nine Song Sparrow subspecies that occur along the Pacific Coast from California all the way up to the outer reaches of Alaska’s islands in the Bering Sea. The genome-sequencing research was conducted at the Cornell Lab’s Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program.

“We found eight gene variations in the genomes we sequenced, all associated with body mass as predicted by Bergmann’s Rule,” says lead author Katherine Carbeck, a PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “What this tells us is that there is a genetic basis for Song Sparrow adaptation to local climate conditions, stretching from the coldest locations in the far north to the warmest parts of its range in California.”

Understanding the nuances of microevolution makes a difference when it comes to conservation, the scientists said. For example, eBird Trends maps show that Song Sparrow populations in northwestern regions, such as Alaska and British Columbia, are stable or increasing currently, but sparrow populations in California are declining.

While declines in one portion of the Song Sparrow’s range could mean loss of genetic diversity in locally specialized populations, Peter Arcese, a coauthor on the study and professor in UBC’s Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences, says the findings suggest a resilient future for these birds—as long as they have habitat.

“Our findings imply that some, if not all, locally adapted Song Sparrow populations may continue to adapt to climate change, as long as we maintain habitat conditions that facilitate the movement of individuals and genes between populations,” he says.

“These genomic discoveries show that Song Sparrows have been waxing and waning over millennia. Over that time, each sparrow population has become beautifully fine-tuned to its local environment,” adds Irby Lovette, another coauthor on the study and director of the Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program at the Cornell Lab. “So the valid concern is that as environments change we might lose those tightly matched adaptations.

“Yet the good news is that this very same genetic mosaic creates the raw material for the sparrows of the future to adapt more quickly, just as long as their populations remain healthy overall such that they can move around to match their traits to changing local conditions.”

This study is the first result of a larger Cornell Lab research effort to sequence Song Sparrow genomes from across North America, spanning nearly all of the 25 recognized subspecies.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library