A Day in the Life of the Cornell Lab

By Miyoko Chu

From the Winter 2015 issue of Living Bird magazine.

January 15, 2015

It’s a typical day at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. As I pull into the parking lot, I see ornithologist Kevin McGowan stepping out of his white Subaru. He tosses a handful of shelled peanuts on the gravel, then scans with his binoculars as the crows come in. It’s his way of making amends. For 26 years, he’s studied the local crows, climbing trees to peer into their nests, measure their young, and mark the nestlings with uniquely numbered leg bands and wing tags. The crows know him and his car as trouble—but they’ll also stop by for a peanut.

Like Kevin, most people coming to work at the Lab today would rather be outside watching birds. They come here, though, because the Lab’s home—the Imogene P. Johnson Center for Birds and Biodiversity, overlooking Sapsucker Woods Pond—is a place where anyone who is curious and passionate about birds and other wildlife can ask questions, discover answers, and take part in advancing the understanding and conservation of the natural world.

Each day, more than 150 people will enter the Lab of Ornithology through the staff entrance: biologists, engineers, computer scientists, educators, web and multimedia producers, writers, artists, and students on a mission to “interpret and conserve the earth’s biological diversity through research, education, and citizen science focused on birds.” But it’s not just about the people in the building. Cornell University’s motto, “Any person, any study,” embraces learning for all—and the rest of world is already at work, connecting with the Lab from afar. At all hours of the day, observations from citizen-science participants pour in to the Lab’s servers from around the globe and information about birds flows out to millions of people through the Lab’s websites. Today, people from all walks of life will interact with one another and the Lab’s staff through live Bird Cams; they’ll join live webinars with Kevin about raptor identification; and kids will watch birds and engage in scientific inquiry with the Lab’s curricula in classrooms across the hemisphere.

You’ll find the staff entrance to the Lab beside a loading dock—a glass door that leads into a hallway with a view of Sapsucker Woods Pond at the other end. If you could see through the ceiling and the walls on either side of you, you’d find yourself surrounded by 1.25 million fish, 800 species of reptiles and amphibians, birds from 134 countries, and 102 families of mammals in the collection of the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates, housed at the Lab. Scientists and students use this invaluable collection for biodiversity research, conservation, and education. But I want to show you another kind of museum today—a museum of animal behavior.

Let’s walk down the hallway to the Macaulay Library, home of the world’s largest collection of natural sounds and video. The heart of the Macaulay Library is an open room with a large table, often piled high with equipment on its way to or from expeditions around the world—recorders, microphones, video cameras, and cases. Displayed on the shelves above are dozens of recorders, a testament to the Lab’s past innovations resulting in the first portable audio recorders and the dish-shaped parabola, repurposed to capture the sounds of birds from equipment used to detect enemy aircraft in World War I.

Since then, volunteer recordists have traveled the world, amassing more than 200,000 audio and video recordings in the collection, each one annotated and archived as carefully as a museum specimen. As you walk past more than a dozen studios that ring the Macaulay Library, you can hear animals from a different part of the world in every studio. Today, media specialist Martha Fischer watches waveforms scroll across her screen, checking the loudness of recordings as she digitizes the pant-hoots of chimpanzees recorded more than 40 years ago in Tanzania. In a video studio, Ben Clock reviews footage of a Snowy Egret snapping up sand fleas on a beach, the high-speed frames revealing how the egret captures the jumping fleas in midair. The video was shot by Cornell undergraduates on a recent expedition to California, led by Ben to teach them techniques in multimedia scientific collecting. Around the corner in a multimedia productions studio, Karen Rodriguez reviews stunning, close-up footage of a Philippine Eagle flying to its nest. She’s part of a team working on a documentary to bring the story of these magnificent eagles to people in the Philippines and internationally to inspire protection for these endangered birds.

Now, step across the hallway into the Bioacoustics Research Program, the largest department at the Lab. It looks like a NASA room with banks of computers and analysts gazing at the screens, but these scientists are listening to the sounds of the earth. Here they can monitor the calls of right whales in Massachusetts Bay in real time, detected by underwater recorders designed by the Lab’s engineers and transmitted by satellite signals. When the analysts detect right whales in shipping lanes, they send an alert for ship captains to slow down to avert collisions with this endangered species.

One hundred years ago, the sounds of wildlife were as ephemeral as the wind; scientists had no way to capture and study them. In the adjacent offices here, programmers and engineers are making unprecedented advances in the automatic detection, visualization, and classification of wildlife sounds—whether the songs of whales, the infrasonic rumbling of elephants, or the fleeting calls of nightmigrating birds. In their latest breakthrough, the Lab’s engineers have adapted their marine acoustic detectors to recognize the sound of chickadees—and have installed the first prototype in the Lab’s bird-feeding garden. Imagine a day when entire networks of affordable, portable smart recorders might generate a real-time inventory of birds vocalizing across a landscape. It’s just one of the many ways that new inventions may completely change the way we listen to and understand wildlife.

Leaving the realm of sound, let’s travel down the hall and around a corner to the Fuller Evolutionary Biology laboratory, where researchers unravel mysteries from evidence too small to see. Today, Bronwyn Butcher is showing undergraduate Sophie Nicolich-Henkin how to extract bird DNA from blood samples as part of her honors thesis project. From these tiny vials of clear liquid, Lab scientists can explore the entire avian genome using techniques initially developed to study human genetic variation. These studies of bird DNA can reveal simple information—like the sex of the Florida Scrub-Jay nestlings that Sophie is assaying—along with much more intricate patterns of genetic diversity and change. The Lab’s researchers have used these tools to explore the mating patterns of dozens of bird species, generate landmark studies of the family trees of wood-warblers and tanagers, discover bird populations that are so genetically distinct that they are classified as new species, and track how endangered birds move among patches of remnant habitat. Some of their most ambitious research uses DNA to study the process of speciation in groups such as chickadees, warblers, and seedeaters, tracking what parts of the genome are involved in making new species different from one another.

From the DNA lab, climb the stairs to the next floor so I can show you where the graduate students sit—but not because there is much to see. At any given time you might find students at their desks, crunching data from their field work—but you’ll also see the empty desks of students still in the field. Taza Schaming is out tracking Clark’s Nutcrackers in the mountains of Wyoming to investigate how the birds are faring as whitebark pine forests die from invasive disease and pine beetle infestations. In the highlands of Guatemala, Gemara Gifford works with local communities to identify agricultural practices that can support livelihoods and conserve forest birds. Some 30 graduate students, 50 undergraduates, and 12 postdoctoral researchers work at the Lab each year. They are the Lab’s lifeblood, bringing fresh ideas and energy to new quests. The scale of their global reach and impact has grown as year after year they generate discoveries and go on to work as leaders in science, policy, communications, and biodiversity conservation.

Around the bend, we’ll enter the realm of the Lab’s public participation programs in citizen science, K–12 science education, and lifelong learning. The open floor spans the entire building, the neat rows of office cubicles adorned with posters of birds and research results. If you are one of the hundreds of thousands of people who have submitted data to a project such as eBird, NestWatch, or Project FeederWatch, this is where scientists analyze your data to reveal new discoveries about birds. Today, FeederWatch project leader Emma Grieg is looking for trends in participants’ reports of Anna’s Hummingbirds. “See these lines?” she says, pointing to a graph on her computer. “Since 1996, the species has moved north into Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Could it be because of climate change? Or more people putting out feeders? These are just some of the factors we’re looking at,” she says.

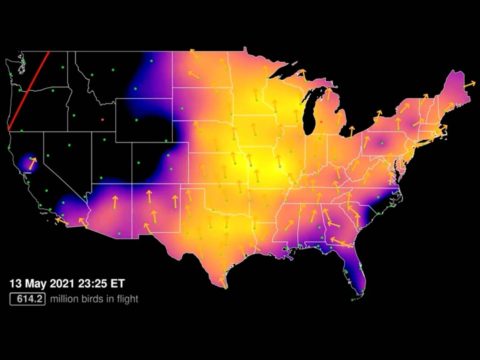

Up on the mezzanine, high above Sapsucker Woods Pond, database managers, programmers, computer scientists, researchers, and statisticians manage the data pouring in from eBird participants around the world, more than 200 million observations since 2002. Today, postdoctoral researcher Alison Johnston is excited about what the data are showing. For the first time, Ali and collaborators have found new ways to mathematically generate models showing not just presence of multiple bird species, but their abundance. “This is really exciting,” she says, “because these data are already being used to target the provision of foraging habitat for migratory shorebirds. Rice farmers are flooding their fields to coincide with when the highest number of birds are migrating. This is what the Lab is so good at doing—uniquely combining science, innovative conservation, and participation from bird watchers.”

From the mezzanine’s rail, look out over the floor below, where dozens of people are at work to bring the world of birds to your desktops, tablets, and smartphones: you can see the computer screens of designers, programmers, educators, writers, and digital content managers bringing birds to life through online experiences such as live webinars, Bird Cams, the Merlin Bird ID app, and the All About Birds website. The portal to the Lab is open 24/7, giving millions of people the anywhere-anytime ability to record their observations, to share in new discoveries, or to find inspiration in the world of birds.

Leaving the offices behind now, walk down the wooden staircase into the Lab’s visitor center. Light from the observatory’s windows pours into the soaring space. Everything here seems designed as a tribute to birds, bringing their beauty and sounds inside. Artist Jane Kim, creator of Ink Dwell Studio, is perched on a hydraulic scissor lift, painting a 10-foot-tall North Island Giant Moa on the wall. This extinct bird from New Zealand is one of the first birds to be painted in her epic mural, a tribute to the world’s 243 families of birds and their ancestors, spanning 375 million years. Around the corner, the wail of a loon emanates from a wooden sculpture, the Sound Ring, designed by renowned artist Maya Lin as a memorial to vanishing species. You can tap a screen next to the exhibit to be transported through sound to other landscapes around the world.

More than 60,000 visitors come to the Lab each year to enjoy the art, exhibits, and 230-acre Sapsucker Woods Sanctuary. More than 2 million people have also visited Sapsucker Woods online, viewed in real time through the lens of a Bird Cam above the pond as it streams live footage of herons, kingfishers, and other wildlife, night and day through the changing seasons.

As you exit from the Lab’s visitor center, you can walk right up to the bronze sculpture of a Passenger Pigeon opposite the bird-feeding garden, on loan from the Lab’s artist-in-residence Todd McGrain. Touch the smooth metal, warmed in the sun, and follow the bird’s gaze up into the sky. More than a century ago, Passenger Pigeons would have flown above Sapsucker Woods. Todd’s sculpture is a memorial to their extinction, a reminder that we never had a chance to see what was once the world’s most abundant bird. In that moment, you can feel how fleeting the existence of wildlife can be. It helps to know that the Lab is here to unite people who love birds and who are actively using the best available science and technology to reach policy makers, international partners, and the public to make the next century a better one for the protection of wildlife.

Whether you’ve made the trip to come see us in person, or whether you know us best from the pages of Living Bird or the All About Birds website, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology is your place. We hope you’ll keep connecting with us to enhance your enjoyment of birds, share your experience, and help protect nature. This job of learning about birds and looking out for their future is what brings us back here every day. Thanks for joining us from wherever you are.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library