30 Years of Project FeederWatch Yield New Insights About Backyard Birds

Illustrations by Virginia Greene; story by Gustave Axelson

Evening Grosbeak by Raymond Lee via Birdshare. January 11, 2017From the Winter 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Since 1987, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies Canada have partnered on Project FeederWatch to mobilize thousands of citizen scientists across North America to count birds in their backyards over the winter.

Three decades of data provide a comprehensive look at continental wintertime populations of feeder birds over the late 20th and early 21st centuries—including some compelling stories of range expansions and contractions, populations in flux, and birds adapting to changing environments.

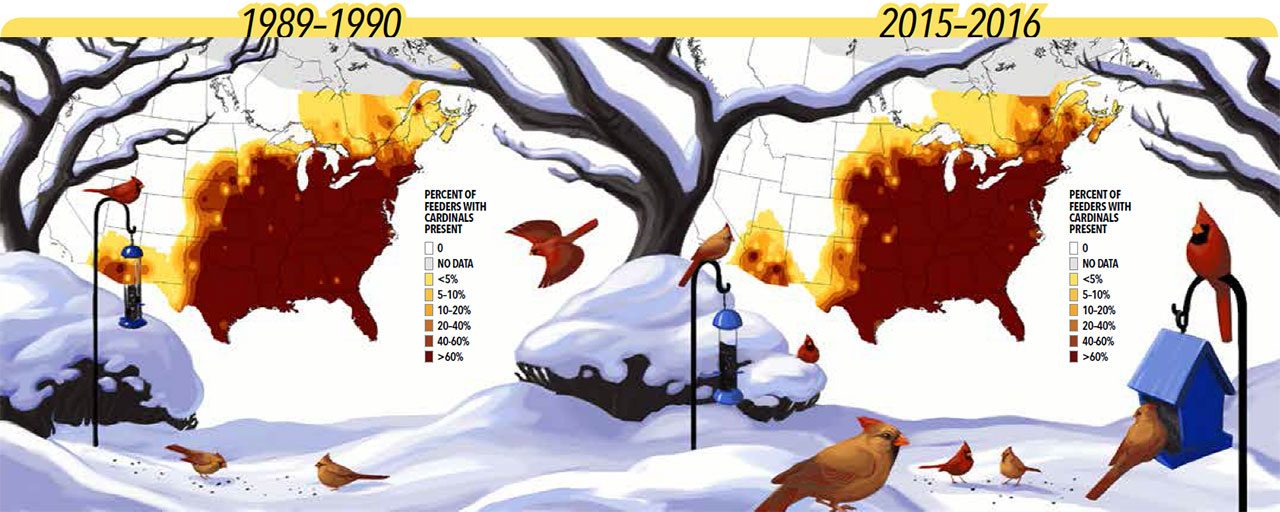

A tale of two species

Northern Cardinals have expanded their range since 1989, as demonstrated by the growing percentage of FeederWatchers reporting cardinals in Minnesota, Michigan, Maine, and southeastern Canada. The colonizing cardinals have pushed farther north by making themselves right at home in suburbia.

“Cardinals, like people, appreciate a free lunch,” says David Bonter, the Cornell Lab’s Arthur A. Allen director of citizen science. “The abundance of food provided by people has helped the species to colonize new areas.”

He says cardinals seem to have benefited from two growing trends among homeowners. More people have bird feeders now than 30 years ago, and more people have landscaped their yards and added shrubbery, which provide fruit for food and shelter for nesting habitat and cover in winter.

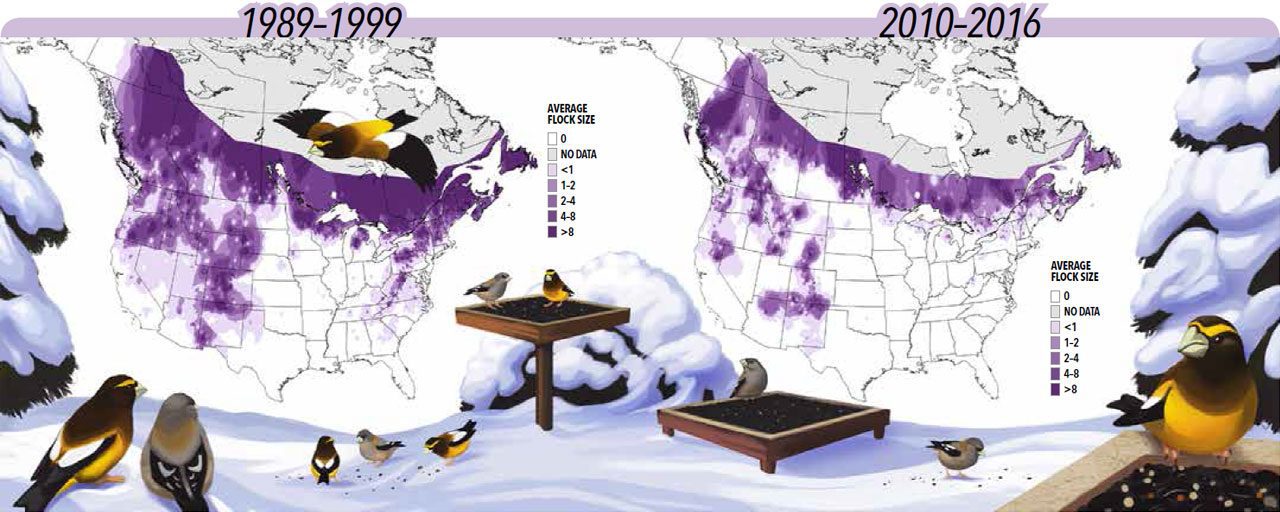

Evening Grosbeak, on the other hand, experienced a range contraction and population decrease. Loss of nesting habitat and food sources may be affecting Evening Grosbeaks, but Bonter says scientists can’t be sure because they nest in the vast, remote boreal forest, where there isn’t much information available about breeding conditions.

“This is an example of how FeederWatch can show us which species are in trouble,” Bonter says, “but other research is needed to understand why.”

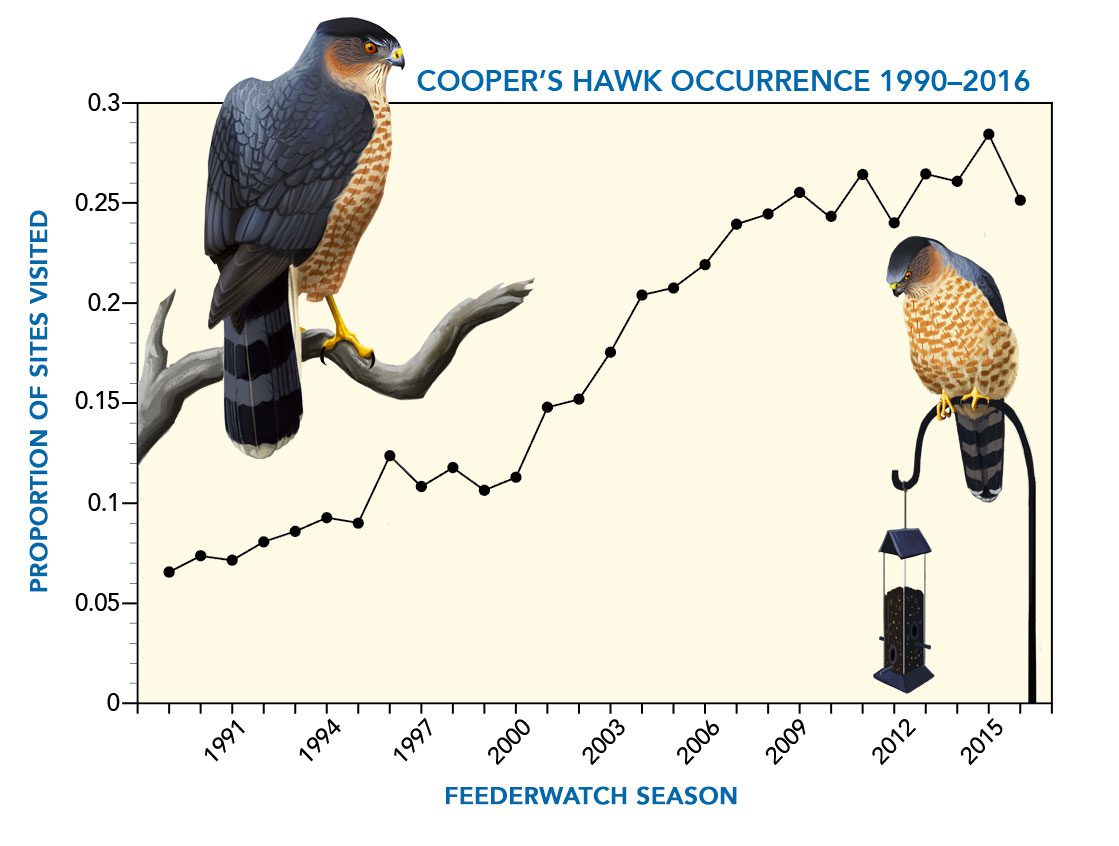

A feeder bird that feasts on feeder birds

Cooper’s Hawk is another species that appears to have gravitated toward backyards with bird feeders, but for a very different reason. The FeederWatch data show a clear and consistent increase in the proportion of backyards hosting these hawks in winter. Emma Greig, FeederWatch project leader, says that the leading hypothesis about this trend focuses on a change in wintering strategy. Instead of migrating to Mexico as so many Cooper’s Hawks did in the past, many appear to be overwintering farther north and are regularly seen in yards and urban habitats. The hawks possibly learned that bird feeders create large groupings of prey.

Even if hawk predation at backyard feeders is occurring more often, however, populations of many of the prey species, such as American Goldfinches and Dark-eyed Juncos, are still stable.

A Northwestern orientation

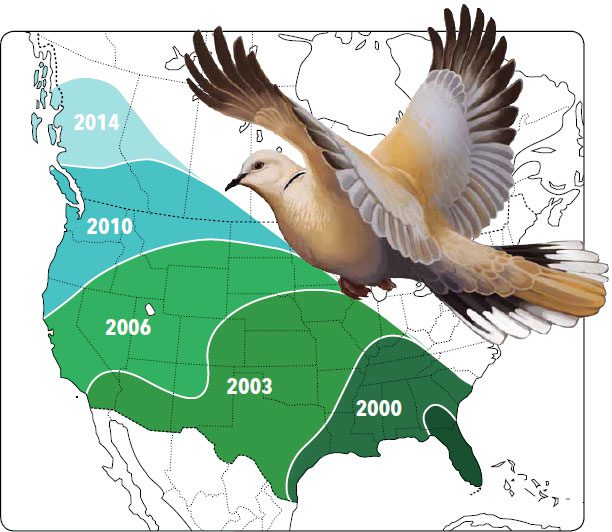

In the mid-1970s, a few Eurasian Collared-Doves—a species native to India, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar—escaped into the wild in the Bahamas during a pet shop robbery. The shop owner eventually let the rest of his flock loose, about 50 birds.

From there, Eurasian Collared-Doves did what they’ve done for centuries: head northwest. From their native India, they expanded to Turkey and then the Balkans in the 1600s, then kept going across Europe in the 1900s, reaching the United Kingdom in 1955. Likewise, Eurasian Collared-Doves wandered northwest from the Bahamas, making landfall in Florida by the 1980s and then amazingly marching across North America all the way to British Columbia in only two decades.

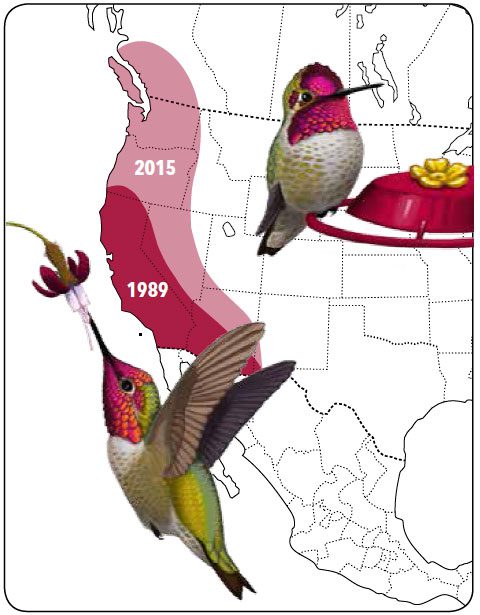

Human-assisted range expansion

The northward march of the Anna’s Hummingbird is doubly amazing. Not only is it a dramatic range increase, but the species now stretching from Baja California to British Columbia is a petite hummingbird that should (theoretically) be limited by cold temperatures and seasonal food availability. They can live with chilly northern weather by entering a state of torpor at night, conserving energy by slowing their breathing and heart rates. When temperatures warm up, they can become active again within a few minutes.

As for finding food in winter, people appear to have helped Anna’s Hummingbirds by putting up hummingbird feeders and planting flowers in gardens. Greig conducted an analysis that showed the locations of Anna’s Hummingbird sightings in the northern part of their range frequently fall within human-populated areas, whereas sightings are spread out across urban and natural areas in Southern California and the Southwest.

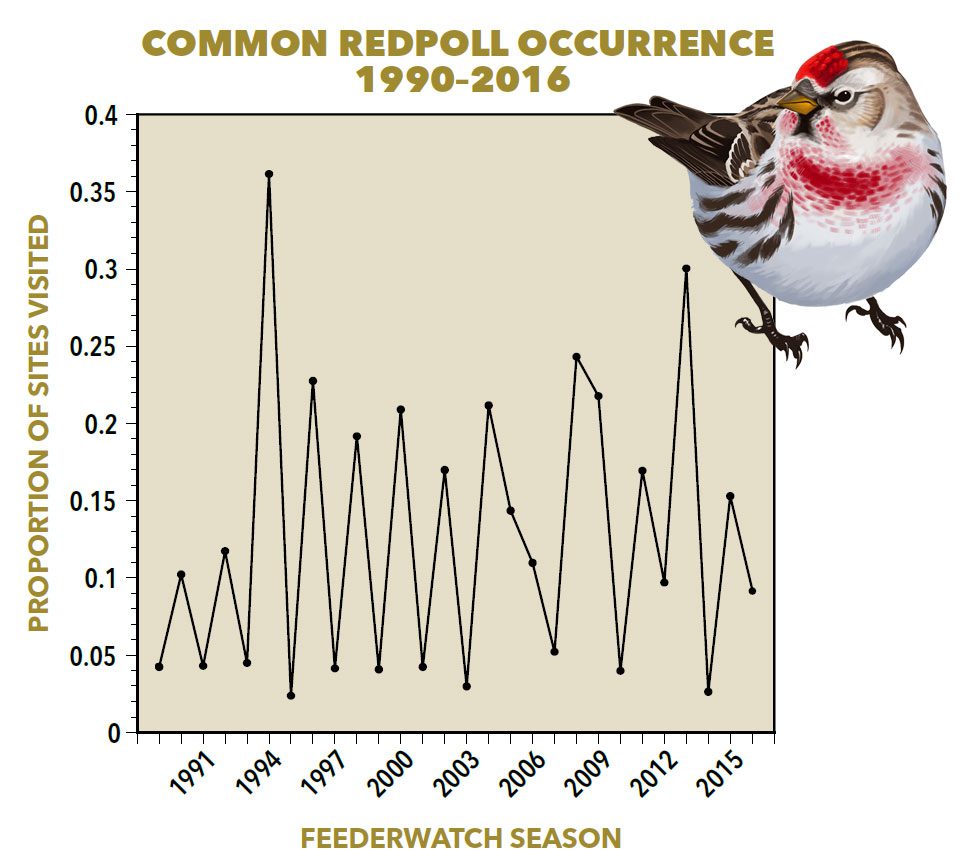

Irregularity in irruptions

It used to be that redpoll irruptions happened every other year like clockwork. One winter none, the next a bounty of redpolls eating nyjer seed at backyard bird feeders. But starting in 2005, some of the FeederWatch counts in low-redpoll years have been higher than expected.

Redpolls tend to winter in the boreal forest. Evidence suggests that they move farther south into southern Canada and the U.S.A when aspen and birch seed crops are lower than required to sustain populations throughout the winter. Those boreal seed crops have a boom-bust cycle, so scientists believe that drove the every-other-year irruptions of redpolls.

The disruption of that pattern “suggests to me that the pattern of food availability in the boreal forest is becoming less reliable,” says Greig.

How well redpolls can weather that change is another question, as yet unanswered. Future counts of redpolls that show up at feeders could provide a relative barometer for redpoll population trends—a great reason to keep FeederWatching for the next 30 years.

Count Birds for Science

Through Project FeederWatch, you can become the biologist of your own backyard. For the $18 fee ($15 for Cornell Lab members), U.S. participants receive the FeederWatch Handbook with tips on how to successfully attract and identify common feeder birds. Participants also receive Winter Bird Highlights, an annual summary of FeederWatch findings. The fee is $35 in Canada and includes a Bird Studies Canada membership. Visit feederwatch.org to learn more.

Related Analysis

Project leader Emma Greig puts FeederWatch data to use to answer the question Do Bird Feeders Help or Hurt Birds? Read her analysis.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library