The Basics of Bird Migration: How, Why, and Where

August 1, 2021Originally published January 2007; updated August 2021.

Geese winging their way south in wrinkled V-shaped flocks is perhaps the classic picture of migration—the annual, large-scale movement of birds between their breeding (summer) homes and their nonbreeding (winter) grounds. But geese are far from our only migratory birds. Of the more than 650 species of North American breeding birds, more than half are migratory.

Why do birds migrate?

People should know that not all birds migrate.

Some birds just stay in the same place all year long. So if we think about the birds up in the boreal forest, the chickadees stay there all year round. They can find, believe it or not, insect eggs and little things like that in the bark, that they can find enough food to keep them, keep them going during the winter. But a lot of the other birds feed on flying insects or moving insects, and there aren’t too many of those, up in Canada in the wintertime, so they have to go somewhere else to find food. Migration is almost always about finding food. It’s not to get out of the cold because birds can survive cold. But there are certain inhospitable places that they need to leave. But it’s almost always about food.

[text on screen: What prompts birds to start migrating?]Well, the thing that starts bird migration usually is a change in daylight and what that does is that starts this sort of, the, the proximate mechanism that gets the birds brains changing, different hormones being produced, and the birds can sense even very small changes in daylight length. There’s this cool term that’s in German called Zugunruhe and that means migratory restlessness.

[text on screen: Zugunruhe. Migratory Restlessness]And so we can you can watch this. And it’s been well studied in birds that if you keep them in captivity, as the light changes, as the days get smaller or longer, they start to get antsy and they just kind of move around in their cages and they just want to go somewhere. And it’s just this need to, to go further, to go further, go south, go south, go down, you know.

[text on screen: How variable is migration timing?]In fact it’s actually fairly rigorous in some species. It’s very, very predictable. Like when Red-winged Blackbirds turn up in central New York, is is always within a two week period. And so some of these things are very precise. However, migration on, you know, for an individual bird depends on the, circumstances that that bird is in. And that includes changes in weather and, and local conditions and stuff like that. So there’s always that sort of fine tuning. So it’s never precisely the same.

[text on screen: Do adult and juvenile birds migrate together?]Yeah, that’s an interesting thing about migration is we tend to think, oh well, yeah, they just go—But they don’t There are different… different… the sexes do different things. And the juveniles do different things. And typically what you see going first are the males, the breeding males of a lot of different birds leave the breeding grounds before the females or the juveniles do. And then as a… again, as a general rule of thumb the adults leave first and then the juveniles leave later. And it may be they just need a longer time to fatten up, to migrate. But that’s very a very predictable pattern that we see

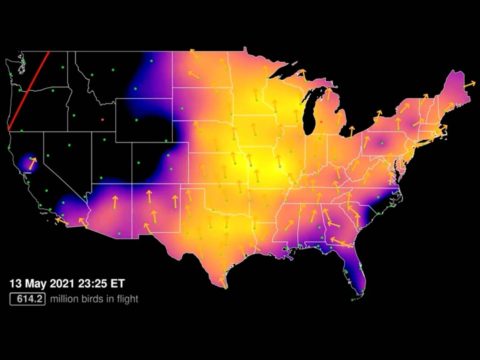

[text on screen: What’s the best time of day to migrate?] [image: map of continental United States in purple, orange, and yellow against a black background, colors indicate predicted strength of bird migration. Text on screen: Migration intensity scale: white = High; yellow to orange = Medium; purple = Low; dark = None. 378 million birds predicted. Logo: BirdCast]Different birds do migrate at different times of the day. And to, a lot of people are surprised to know that the the bulk of migration happens at night, that most birds fly at night. And there’s several reasons for this. One is that they, you know, there are fewer predators being able to catch you at night. You can’t really forage that much, so you might as well fly.

[Image: graphic of a flying Yellow Warbler against a globe depicting lines of magnetic force]When there’s not enough light to see very well, birds can actually turn on a different sense and see the magnetic fields of the earth. And so they can tell north and south, because they can see the magnetic fields. I read that news and it’s like, oh, that’s why they fly at night is because then they can see. And that does seem to be the consensus is that, a lot of the nighttime flying, is because that allows them to use their magnetic sense to detect north and south.

[text on screen: How can people help migrating birds?]Well, hummingbird feeders, the hummingbirds really like hummingbird feeders, and you won’t make them stop migrating, and stick with it and stick with your feeder till it gets cold. They’re not going to do that. But they will use it as a source of, cheap energy that they can put on and, and, help them along their way. Suet for some of the other birds is good. The other thing to do to help birds along during this is turn off your lights at night. That’s a big one. And of course, this really plays out in the cities. And, and there are the programs that people have, a number of organizations are working with, including the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, that are trying to encourage big cities to cut down on their light usage during peak migration time because birds get confused. And so turn off your lights at night, plant native plants, put up a hummingbird feeder. That doesn’t do it all. But there are a couple of tangible things that people can do.

[text on screen: Media Credits: Oregon soundscape by Todd Sanders / Macaulay Library; Sandhill Cranes by Dylan S. / Macaulay Library; Blaack-capped Chickadee by Nick Saunders / Macaulay Library; Tree Swallow by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library; Whimbrels by Matt Aeberhard / Macaulay Library; Red-winged Blackbirds by Ron Beurkert / Macaulay Library; American Avocets by Matt Zuro / Macaulay Library; BirdCast Migration Forecast 6 Sept 2024 / Cornell Lab and Colorado State University; Geomagnetic illustration by Jillian Ditner / Cornell Lab; Calliope Hummingbird by Joshua Glant / Macaulay Library; Nighttime view from space by NASA / JPL.] [soundscape of bird calls ends]End of Transcript

Birds migrate to move from areas of low or decreasing resources to areas of high or increasing resources. The two primary resources being sought are food and nesting locations. Here’s more about how migration evolved.

Birds that nest in the Northern Hemisphere tend to migrate northward in the spring to take advantage of burgeoning insect populations, budding plants and an abundance of nesting locations. As winter approaches and the availability of insects and other food drops, the birds move south again. Escaping the cold is a motivating factor but many species, including hummingbirds, can withstand freezing temperatures as long as an adequate supply of food is available.

Types of migration

The term migration describes periodic, large-scale movements of populations of animals. One way to look at migration is to consider the distances traveled. The pattern of migration can vary within each category, but is most variable in short and medium distance migrants. Long-distance migrants face arduous journeys, yet it is undertaken by about 350 species of North American birds.

Permanent residents do not migrate. They are able to find adequate supplies of food year-round.

Short-distance migrants make relatively small movements, as from higher to lower elevations on a mountainside.

Medium-distance migrants cover distances that span a few hundred miles.

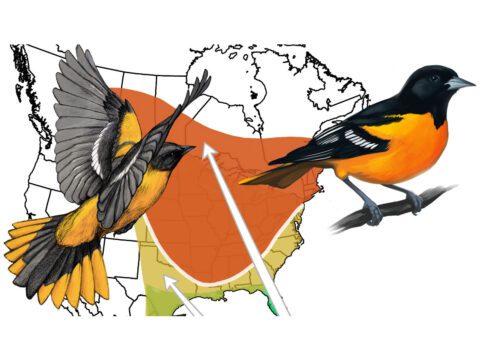

Long-distance migrants typically move from breeding ranges in the United States and Canada to wintering grounds in Central and South America.

Origins of long-distance migration

While short-distance migration probably developed from a fairly simple need for food, the origins of long-distant migration patterns are much more complex. They’ve evolved over thousands of years and are controlled at least partially by the genetic makeup of the birds. They also incorporate responses to weather, geography, food sources, day length, and other factors.

For birds that winter in the tropics, it seems strange to imagine leaving home and embarking on a migration north. Why make such an arduous trip north in spring? One idea is that through many generations the tropical ancestors of these birds dispersed from their tropical breeding sites northward. The seasonal abundance of insect food and greater day length allowed them to raise more young (4–6 on average) than their stay-at-home tropical relatives (2–3 on average). As their breeding zones moved north during periods of glacial retreat, the birds continued to return to their tropical homes as winter weather and declining food supplies made life more difficult. Supporting this theory is the fact that most North American vireos, flycatchers, tanagers, warblers, orioles, and swallows have evolved from forms that originated in the tropics.

What triggers migration?

The mechanisms initiating migratory behavior vary and are not always completely understood. Migration can be triggered by a combination of changes in day length, lower temperatures, changes in food supplies, and genetic predisposition. For centuries, people who have kept cage birds have noticed that the migratory species go through a period of restlessness each spring and fall, repeatedly fluttering toward one side of their cage. German behavioral scientists gave this behavior the name zugunruhe, meaning migratory restlessness. Different species of birds and even segments of the population within the same species may follow different migratory patterns.

How do birds navigate?

Migrating birds can cover thousands of miles in their annual travels, often traveling the same course year after year with little deviation. First-year birds often make their very first migration on their own. Somehow they can find their winter home despite never having seen it before, and return the following spring to where they were born.

The secrets of their amazing navigational skills aren’t fully understood, partly because birds combine several different types of senses when they navigate. Birds can get compass information from the sun, the stars, and by sensing the earth’s magnetic field. They also get information from the position of the setting sun and from landmarks seen during the day. There’s even evidence that sense of smell plays a role, at least for homing pigeons.

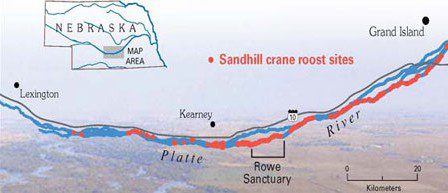

Some species, particularly waterfowl and cranes, follow preferred pathways on their annual migrations. These pathways are often related to important stopover locations that provide food supplies critical to the birds’ survival. Smaller birds tend to migrate in broad fronts across the landscape. Studies using eBird data have revealed that many small birds take different routes in spring and fall, to take advantage of seasonal patterns in weather and food.

Migration hazards

Taking a journey that can stretch to a round-trip distance of several thousand miles is a dangerous and arduous undertaking. It is an effort that tests both the birds’ physical and mental capabilities. The physical stress of the trip, lack of adequate food supplies along the way, bad weather, and increased exposure to predators all add to the hazards of the journey.

In recent decades long-distant migrants have been facing a growing threat from communication towers and tall buildings. Many species are attracted to the lights of tall buildings and millions are killed each year in collisions with the structures. The Fatal Light Awareness Program, based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and BirdCast’s Lights Out project, have more about this problem.

Studying migration

Scientists use several techniques in studying migration, including banding, satellite tracking, and a relatively new method involving lightweight devices known as geolocators. One of the goals is to locate important stopover and wintering locations. Once identified, steps can be taken to protect and save these key locations.

Each spring approximately 500,000 Sandhill Cranes and some endangered Whooping Cranes use the Central Platte River Valley in Nebraska as a staging habitat during their migration north to breeding and nesting grounds in Canada, Alaska, and the Siberian Arctic.

What is a migrant trap?

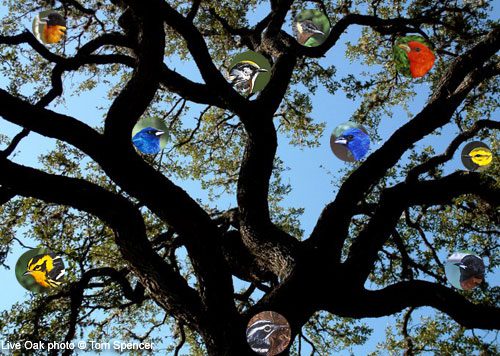

Some places seem to have a knack for concentrating migrating birds in larger than normal numbers. These “migrant traps” often become well known as birding hotspots. This is typically the result of local weather conditions, an abundance of food, or the local topography.

For example, small songbirds migrating north in the spring fly directly over the Gulf of Mexico, landing on the coastlines of the Gulf Coast states. When, storms or cold fronts bring headwinds, these birds can be near exhaustion when they reach land. In such cases they head for the nearest location offering food and cover—typically live-oak groves on barrier islands, where very large numbers of migrants can collect in what’s known as a “fallout.” These migration traps have become very popular with birders, even earning international reputations.

Peninsulas can also concentrate migrating birds as they follow the land and then pause before launching over water. This explains why places like Point Pelee, Ontario; the Florida Keys; Point Reyes, California; and Cape May, New Jersey have great reputations as migration hotspots.

Spring migration is an especially good time for those that feed birds in their backyard to attract species they normally do not see. Offering a variety of food sources, water, and adding natural food sources to the landscape can make a backyard attractive to migrating songbirds.

Range maps

It’s always a good idea to use the range maps in your field guide to determine if and when a particular species might be around. Range maps are especially useful when working with migratory species. However, they can be confusing: ranges of birds can vary year-to-year, as with irruptive species such as redpolls. Also, the ranges of some species can expand or contract fairly rapidly, with changes occurring in time periods shorter than the republication time of a field guide. (The Eurasian Collared-Dove is the best example of this problem.)

These limitations are beginning to be addressed by data-driven, digital versions of range maps. The maps are made possible by the hundreds of millions of eBird observations submitted by birdwatchers around the world. “Big Data” analyses are allowing scientists to produce animated maps that show a species’ ebb and flow across the continent throughout a calendar year—as well as understand larger patterns of movement.

Additional resources

Migration is a fascinating study and there is much yet to learn. Songbird Journeys, by the Cornell Lab’s Miyoko Chu, explores many aspects of migration in an interesting and easy-to-read style. The Cornell Lab’s Handbook of Bird Biology provides even more information on the amazing phenomenon of bird migration.

More About Bird Migration

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library