The Catbird Seat: Birding’s Endgame: Skill Versus Life List

By Pete Dunne; illustration by Jeff Sipple

October 15, 2013

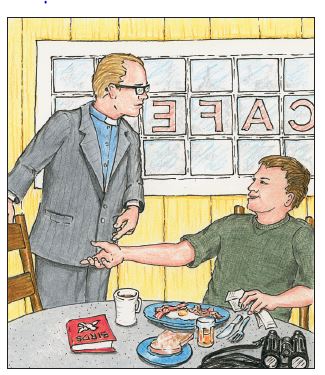

Mind if I join you for break- fast?” the man who identified himself as Jack asked. “Please do,” I replied, gesturing toward an open chair.

“You’re Pete Dunne, right?”

“How did you know that?” I asked.

“You sold me binoculars several years ago,” he explained, which was only half the answer. It turns out that Jack was the Methodist minister on call at the Bacharach Rehabilitation Center where I was doing physical therapy following a stroke in March 2013.

Ministers as a rule have a gift for remembering faces and names—skills that serve their birding focus, too. I now know four men of the cloth whose earthly flock encompasses the birds of the field.

“I don’t have a very big life list,” he replied when I asked if he was also a birder. And I wondered, not for the first time, why it is that this concept of the “life list” has so much significance in the minds of people who watch birds.

I’ve decided it’s a form of communication shorthand. Invoking the word “life list” implies that you have insight into the language and customs of the birding tribe.

While appreciating the avocational implications of his disclosure, I was more delighted by his follow-up qualification. “When I started birding I knew I wouldn’t have the time or money to run up a big list. So instead I concentrated on getting familiar with the birds in my region and becoming a more skilled birder.”

I wondered why it is that these commendable avocational focuses seem always to be trumped by lists.

It’s possible that there may have been a time during bird-watching’s evolution when the most skilled birders also had the most birds in their life lists, so skill and big list were synonymous. But I doubt it. Certainly there are multiple individuals with North American life list totals up in the nosebleed section who are also exceptionally skilled birders. But in looking at my old mentor’s 1947 Peterson Field Guide to the Birds and counting the checks in the boxes of the section entitled “My Life List,” I tally 347 (excluding the Swainson’s Hawk and Brown Booby, whose written in names are qualified by question marks). Although Floyd was one of the finest field birders it has ever been my pleasure to raise glasses beside, he was not well traveled, hence his fairly modest total—one that by modern standards is more in line with a New Jersey big year list than a life list.

Why did the institution of the life list come to assume so much significance?

Thirty years ago, on my first trip west, I was at Ramsey Canyon trying to sort out the nonadult male hummingbirds swarming over the feeders. Seated nearby was a very accomplished and well-traveled local birder who enjoyed the distinction of being the first person to reach 700 species for North America. Seeking his guidance, I noted that I thought female Black- chinned Hummingbirds looked gaunt and long-billed.

“I couldn’t say,” he noted.

Although I was impressed by his candor, I was also surprised by his apparent nonchalance.

Note that this was long before the publication of Steve Howell and Sherry Williamson’s fine guides to hummingbird identification and before Sibley, too. We who are trying to sort out southwestern hummingbirds today have lots of advantages over birders who were grappling with this challenge a quarter-century ago.

My point is not to say that people who are committed listers are not skilled birders. Absolutely not. In fact, most birders I know who are serious about their life list are exceptionally skilled birders.

But a modest life list does not necessarily reflect a lack of dedication or skill. More often it is a reflection of geographic and time constraints. In my case it is a matter of focus exacerbated by poor bookkeeping. Although I can’t say how many birds I have on my North American life list, after a few moments of thought I could almost certainly list all the regularly occurring species that have thus far eluded me.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library