A Swainson’s Hawk Reunion Celebrates a Conservation Success

By Scott Weidensaul

Swainson’s Hawk by Chris Vennum. June 17, 2019From the Summer 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

An hour after dawn, the Butte Valley still lay in a basin of shadow, the July sunrise bright on the rugged, juniper-clad hills to the west, and splashing light on the high, snow-covered double cone of Mount Shasta 40 miles to the south. Below us lay an orderly gridwork of agricultural fields—rows of crops in immense rectangles, circles of green alfalfa surrounding center-pivot irrigation rigs. In the distance was the little town of Dorris, California, just a couple of miles from the Oregon border, where an American flag hung limp in the still air atop what the chamber of commerce brags is, at 200 feet high, the tallest flagpole west of the Mississippi. Beyond it lay sagebrush and summer-dry grass, part of the 18,000-acre Butte Valley National Grassland.

Chris Vennum had a great view, near the top of a tall juniper along one of the hills that encloses the valley, but his mind wasn’t on the scenery. A big female Swainson’s Hawk, screaming her anger in high, piercing wails, was dive-bombing the scientist as he reached into the bird’s bulky stick nest for its lone chick. Even with a bright orange climbing helmet for protection, Vennum ducked each time his ground team shouted a warning and the hawk turned to attack. Pummeled in the past, he’d learned from experience not to take the threat lightly.

It’s the sort of scene I’ve experienced countless times, both as a writer and as a raptor researcher; in decades of field work, I’ve been strafed myself more than once. But the sight of that Swainson’s Hawk overhead—each sooty wing coming to a candle-flame point, the morning light glinting off her dark, chestnut-colored breast and head, her smaller mate circling and calling a bit farther out—brought up potent memories. There was a time, more than two decades ago, when this species faced a terrifyingly imminent danger half a world away, in South America on its wintering grounds. I was with the scientists in Argentina then, and I saw the threat firsthand, but the discovery that saved these hawks was made back here in the sagebrush and farm fields of the Butte Valley in northern California. Twenty years later, I was back to close the loop.

Few raptors on Earth travel as far as Swainson’s Hawks, as much as 12,000 miles a year between the prairies and rangelands of western North America and the pampas of Argentina—a hemispheric journey from one grassland sea to another. In the autumn of 1994, a U.S. Forest Service biologist named Brian Woodbridge used one of the first small satellite transmitters to follow a single hawk from California to its wintering grounds in Argentina. He was worried because in some years, more than a third of the adult Swainson’s Hawks nesting in the Butte Valley failed to return in the spring.

In Argentina, he discovered the species was being decimated by pesticide poisoning. That winter and the next, Woodbridge and his colleagues found tens of thousands of dead hawks in just one small section of the pampas, up to 3,000 dead hawks in a single field, including birds Woodbridge had banded practically in his backyard here in California.

Such devastating losses, experts warned, would rapidly plunge the Swainson’s Hawk toward extinction range-wide. Although they are among the most widespread buteos in North America, virtually the entire species winters in central Argentina, an area perhaps one-sixth the size of its nearly 1.8-million-square-mile breeding range. In Argentina, massive changes in agriculture were already turning a hawk-friendly landscape of pasture and grassland into monocultures of row crops. Then came a grasshopper outbreak, which farmers battled with an organophosphate called monocrotophos. Banned in much of the world, the chemical is astoundingly toxic to birds; many hawks died before they could even completely swallow a poisoned grasshopper.

News of the hawk slaughter generated international outrage, prompting the Argentine government to severely restrict the offending chemical in 1996. The following year, when I spent a month in the pampas working with Woodbridge and a team of American and Argentine scientists—trapping and tagging hawks, following them with radio transmitters, trying to determine how a variety of toxins were affecting them—there was cautious optimism that the danger was passing. In the decades since, the closely monitored Swainson’s Hawk population in the Butte Valley has recovered steadily, eventually surpassing its prepoisoning level.

“You should come out next summer when we’re banding chicks,” Chris Vennum told me when I met him at a raptor research conference a couple years ago. “Brian will be there, all the old crew are coming in to help. It’ll be a reunion.” The next season, he said, would likely set a new record for nests.

So last July I jumped at the chance, and not just to help celebrate a victory lap for a once-threatened bird of prey. The Swainson’s Hawks of Butte Valley have been the subject of a ground-breaking study now in its fifth decade, the work of four generations, so to speak, of scientists, all of whom would be on hand. Their work in this remote valley has produced remarkable insights into the lives of these birds, but has also revealed, in microcosm, many of the larger issues facing any migratory raptor in the 21st century. These most-ardent champions of the Swainson’s Hawk admire the bird’s adaptability and like its odds in a changing world, but at the same time they wonder just how the birds will face an emerging suite of challenges that may be less easily solved than those of the past.

Chris Vennum, a doctoral student at Colorado State University, captures a Swainson’s Hawk nestling to band. Over 1,100 Swainson’s Hawk chicks in the Butte Valley have been color-banded. Photo by Scott Weidensaul.

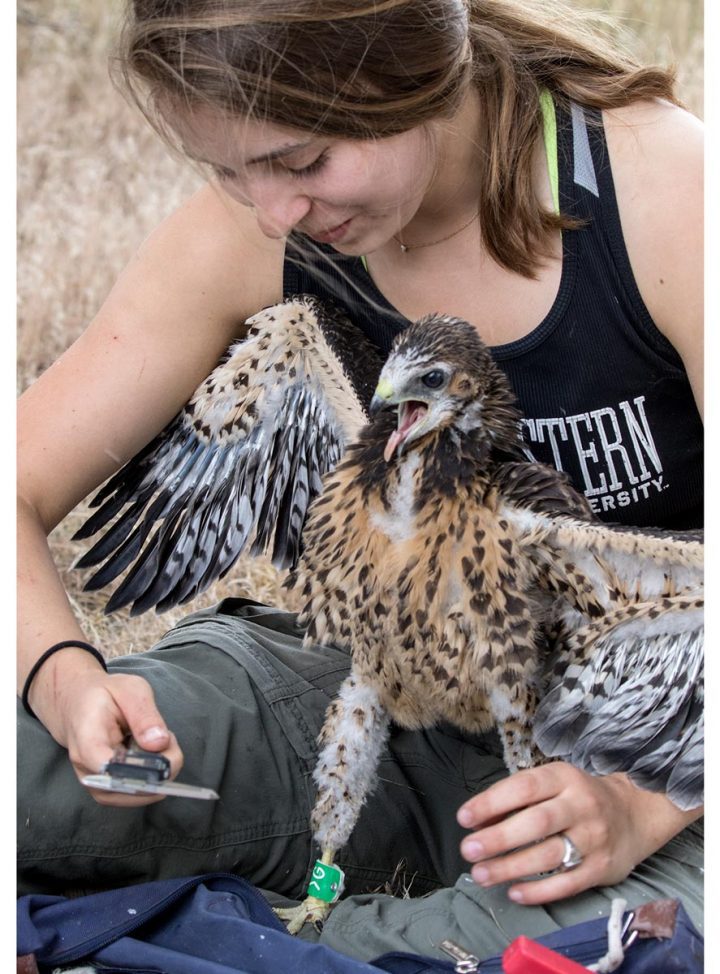

Hamilton College undergraduate Amelia Boyd takes measurements from a color-banded nestling. Photo by Scott Weidensaul.

Vennum lowered the chick, zipped up inside a canvas shoulder bag, to the ground, where Chris Briggs removed it and handed the bird to Amelia Boyd. Almost as heavy as its parents, but with its wing and tail feathers still growing, the nestling filled Boyd’s lap but sat quietly as the young woman banded, weighed, and measured it, protesting only briefly when she pricked a vein beneath its wing for a tiny blood sample. Briggs, a professor at Hamilton College in New York, first came to the Butte Valley’s high desert in the early 2000s, working for Brian Woodbridge. Vennum, in turn, worked with Briggs while getting his master’s degree and now is a doctoral student at Colorado State and in charge of the Swainson’s Hawk project himself. Boyd is a Hamilton undergrad, hired for the summer—the latest twig on this ever-branching scientific family tree.

The hillside nest finished, we drove to a flat expanse of rabbitbrush and sage and hiked out to a dense, bulbous juniper with a nest 40 or 50 feet up. The adult Swainson’s Hawks circled and squealed their displeasure, the visibly larger female hanging closest. Boyd buttoned up a long-sleeved shirt despite the heat—the temperature would top 104 F by late morning—strapped on a helmet and pulled on a pair of gloves, then scrambled up through the tangled, clawing branches that tore at her clothing and skin. When Boyd’s head appeared in a gap in the canopy, the big, dark-morph female hawk saw her chance. “Here she comes…duck!” Vennum shouted. The hawk missed by a foot or two, screaming as she passed.

“Where is she?” Boyd hollered. A pre-med undergrad who signed up for the work because she likes to climb, she had earlier admitted she was pretty freaked out by the prospect of getting clocked on the head, five stories from the ground, by a large bird with eight knives on its feet. “She’s high above you and circling up,” Vennum yelled. “You’re good.” Boyd wasted no time bagging the lone chick in the nest and starting quickly down to safety. When it was returned to the nest a short while later, the chick sported on its right leg a green color band with a white, two-character code—a birth certificate of a kind, one that would be easily readable from a distance, and a key to what makes this long-running study so unusual and important.

Scientists have been scrutinizing the Butte Valley’s Swainson’s Hawks since the late 1970s, when a biologist named Pete Bloom was tasked with conducting exhaustive, statewide surveys of the species for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Although Swainson’s Hawks remained common across most of their range in the first half of the 20th century, they had suffered catastrophic declines in California. Based on his surveys and historical records, Bloom concluded that the Golden State’s Swainson’s population had fallen by more than 90%, from more than 17,000 pairs before settlement to just 400 in 1980, vanishing entirely from all but a few places like the Butte Valley. Habitat loss was believed to have played a big role, but in a prediction that proved prescient, Bloom also speculated that pesticide use on the wintering grounds might also be a factor. Brian Woodbridge, hired first by Bloom in 1981 and the next year by the U.S. Forest Service to study the hawks, would later confirm that hunch.

We’d had a chance to clean up from the hot day’s work when Woodbridge, Bloom—still lean and wiry, though his hair and beard have gone silver-white—and the others arrived that evening. While the burgers grilled, I got an overview of how the research has changed with the years. When Bloom and Woodbridge began 40 years ago, they trapped nesting adults and gave them color bands; nestlings, most of which don’t survive to adulthood, received standard metal leg bands, which are all but impossible to read at a distance. (Those that returned as breeding adults would be trapped and color-banded.) When Briggs came on in 2008, though, he began the arduous task of color-banding almost every chick in every nest they could find, every year, across the 10-by-20-mile valley—almost 1,100 nestlings to date. As a result, more than three-quarters of all the adult Swainson’s Hawks in the immense valley are now color-banded, one of only a few such thoroughly marked raptor populations in the world. The scientists can thus tell, at a glance, which individuals have returned and which have disappeared, whether they’ve shifted territories, and who is paired up with whom or has split from a long-time mate.

Hamilton College biologist Chris Briggs weighs a Swainson’s Hawk. Photo by Scott Weidensaul.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Brian Woodbridge places a leg band on a Swainson’s Hawk. He has been studying the hawks of the Butte Valley since the 1980s. Photo by Scott Weidensaul.

Briggs and Vennum can also now map the valley’s Swainson’s Hawk lineages back through generations and across bloodlines, which has offered some surprising insights into the hawks’ biology and behavior. For one thing, they know this small breeding population is intensely loyal to the Butte Valley; color-banded birds rarely show up anywhere else except the neighboring Klamath Valley a few miles away, a remarkable degree of site fidelity. The researchers have also learned that almost all of these hawks are descended from “super moms,” the one-third of the females in this population that produce virtually all the chicks that survive to adulthood.

“It’s really just a few individuals that are driving this population,” Vennum said the next day, pulling off his climbing helmet and rubbing his buzz-cut blonde hair. “You have a majority of duds that really aren’t contributing much.” Because very few raptor populations are so intensely tracked, no one knows if this is typical of hawks in general or unique to this species and place.

Unlike populations farther east, Swainson’s Hawks in California are predominantly dark-morph birds, exhibiting lovely and highly variable tones of cinnamon, chestnut, and mahogany; light-morph individuals, like those that dominate the rest of the Swainson’s Hawk breeding range, make up fewer than 10% of the population in the Butte Valley. Why this is so—and why so many other buteos, like Red-tailed, Ferruginous, and even Broad-winged Hawks, also exhibit an east-to-west, light-to-dark morph gradient—is something that Briggs obsesses over, without yet having an answer. But because he knows everyone’s family history in the Butte Valley, Briggs has learned that while female Swainson’s Hawks don’t seem to care about the coloration of their mates, males tend to pick females that share the morph pattern of their mothers—a so-called Oedipal complex. Intriguingly, males that pick mates that don’t match their mother’s morph produce significantly fewer fledglings over their lifetimes, which are also shorter than average.

“Whether that means those males are terrible quality and they just can’t attract the females they think are attractive, or [are forced to] the periphery of the valley into some crappy territory, or whether they’re just not willing to put in the effort to a female that they don’t find attractive, we don’t know,” Briggs said. One possibility, though, is that the morph colors may be a visible expression of some aspect of the bird’s immune system so that mismatched morphs might also have mismatched immunity complexes, which in some animals can compromise breeding success. The blood samples that Boyd was taking may answer that question.

Vennum climbed the next nest in a tree near an alfalfa field—the 99th of the season, a new record for the valley. The count would eventually top 101 nests, but it was far from a record year in terms of productivity; many nests had failed, and in those that did make it, single chicks were the rule. It had been a dry year, which appears to have driven down rodent numbers, especially on native grasslands where most of the nest failures occurred. Such ups and downs are normal for rodents and raptors, but in the Butte Valley, Swainson’s Hawks have an agricultural lifeline in the form of those luminously green alfalfa fields.

If four decades of research in the Butte Valley has demonstrated anything, it is the fundamental link between hawks, rodents, and alfalfa—one of the economic mainstays of this region. High milk prices in the 1990s sparked a demand for hay to supply dairy operations, Brian Woodbridge told me the following day as we scouted for unbanded adult hawks to trap. What had been weedy potato fields when he first arrived in the valley quickly blossomed into huge, round circles of heavily irrigated alfalfa. All that green is perfect habitat for Belding’s ground squirrels, which exist here in astounding densities of up to 133 squirrels per acre, and which are in turn ideal prey for raptors of all sorts.

“Any increase in alfalfa productivity is an increase in Swainson’s Hawk populations,” Woodbridge said. “Everywhere they live, swainies use ag habitats. It’s amazing, the degree of reliance on ag habitats in this bird. It’s pretty much 100%. These two communities, the hawks and the farmers, fit together for better or worse.”

It’s obviously been some of each, as those poisoned hawks in Argentina proved. But telemetry since the 1990s, especially new work that Chris Vennum has done tracking young Swainson’s Hawks for the first time, has demonstrated the importance of irrigated alfalfa. On migration, the hawks zero in on areas which, even from space, show the giant green-circle signature of alfalfa fields, where they stop, rest, and feed. Regions where such agriculture is scarce are often literal flyover country for Swainson’s Hawks, which don’t linger on the way.

Much of the Butte Valley’s 130 square miles was originally an immense wetland dotted with sagebrush islands, marginal habitat for a grassland raptor. But beginning in the 1860s, settlers drained the tule marshes and converted the land to farming and ranching, opening a door for Swainson’s Hawks. Alfalfa supercharged the process.

Today, however, the new boom in the Butte Valley is strawberries—and that could be a troubling change for the raptors there. The valley is only one link, albeit a critical one, in a strawberry cultivation chain stretching the length of California—a dizzyingly complex, labor-, transport- and chemical-intensive process that keeps ripe berries on American tables. Plants grown from clusters of cloned cells and raised first in greenhouses and then in fields in the hot Central Valley are dug up and trucked north to the much cooler Butte Valley. Their offshoots, known as “daughter” plants, are primed by the chilly nights and warm days here to flower, but before they do so they are hauled as much as 400 miles back south and replanted, producing the big, if rather insipid, berries that fill supermarkets.

Strawberry-growing started in the Butte Valley about 15 years ago, Vennum said, but has really taken off in the past decade. The immediate concern to biologists is the sterility of the land it requires—literally so, as the berry fields are covered with plastic and fumigated with fungicides before planting.

“Nothing uses them,” Vennum said, “Not squirrels, not hawks. Nothing.”

At the moment, the berry production is mostly confined to a few thousand acres of the valley, and the hawks still have other options. But strawberries are even more water-dependent than alfalfa, and while Woodbridge told me the current level of irrigation pumping is thought to be sustainable, climatologists predict a dramatically reduced snowpack in northern California in the years ahead.

Twenty years after their near-brush with catastrophe in Argentina, Swainson’s Hawks are riding high across their range, but their history is a reminder that with every mile a migratory bird has to travel, the chance that something crucial will change along its route increases. Biologists know the hawks’ destiny is, like farming, bound up with the availability of water in an increasingly warm and often arid world, but they are cautiously optimistic about its chances.

“This is a bird that has adapted really well to agriculture, even becoming urban in some areas,” Vennum said. In parts of California, as well as the Canadian prairies, the hawks have even started nesting in residential neighborhoods near suitable hunting habitat.

A world with 9 billion people in it by 2050 could look quite different to Swainson’s Hawks—more agriculture and more cities—but Vennum said these hawks have proven their powers to adapt and survive: “This is one species that could do really well in that situation.”

Scott Weidensaul has written more than 30 books and studies the movements of owls, hummingbirds, and other migratory birds. His latest book, coming in 2020, will explore global migratory bird conservation.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library