When Goshawks Ruled the Autumn Skies

Story by Scott Weidensaul; Photos by Dudley Edmondson

September 22, 2022Are the massive migration flights of Northern Goshawks a thing of the past? Some scientists think climate change and habitat loss have made these big accipiters permanently scarce. But others see a complex pattern of cycles within cycles, and the possibility that the mega flights will return.

From the Autumn 2022 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

It was one of those migration season mornings when you’re not sure where to look next. Overnight, a flood of songbirds had surged across New England, and I was in a happy daze standing in the front yard, trying to keep up with waves of warblers, vireos, tanagers, grosbeaks, and thrushes passing through the trees around me.

Then in a flash, everything went still. From down our long, wooded lane, I heard screaming jays and a host of alarm calls that grew louder and closer. A huge blue-gray raptor, its black head set off by ivory-white eyebrows, swept up the middle of the driveway at head height, pursued by the sounds of avian indignation. The goshawk passed within just eight or 10 feet of me, never giving me a glance from its blood-red eyes, then disappeared back into the woods.

Here in southern New Hampshire, the Northern Goshawk—the biggest and heaviest of the world’s 50-some accipiter species, a circumboreal raptor renowned for its predatory flair and tenacity—is at best an uncommon breeder. But I see them often enough that I’m confident they nest in the large expanse of beech-hemlock forest that lies out my back door. In the weeks that followed this most recent encounter, I spent hours slipping quietly through those woods looking for any local goshawks.

My connections with goshawks go back a long way. An avid teenaged hawkwatcher, I saw my first “gos” on a blustery October afternoon in 1976 at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Pennsylvania. In the late 1980s and 90s, I began trapping and banding migrant raptors along that ridge, first with the sanctuary’s research team and later for my own migration research; goshawks were the occasional and always exciting cherry on a great day. They are flashy and powerful, fearless, and memorable. In the words of one banding colleague: “Every gos is a story.”

And theirs has been an interesting one. Over the past two centuries goshawks rode a rollercoaster of persecution and conservation across many parts of their global range, experiencing drastically changing fortunes, range contractions, and range expansions. They have been the focus of intensive research and sometimes acrimonious litigation over their proper management, with big implications for forestry and timbering in places like the Pacific Northwest and Southwestern mountains. Once eliminated from parts of the East and Upper Midwest, goshawks underwent a renaissance of sorts in the late 20th century, reoccupying landscapes from which they’d been absent for generations. But now it seems some of those gains may have been rolled back by an exotic disease and, perhaps, another equally fierce predator.

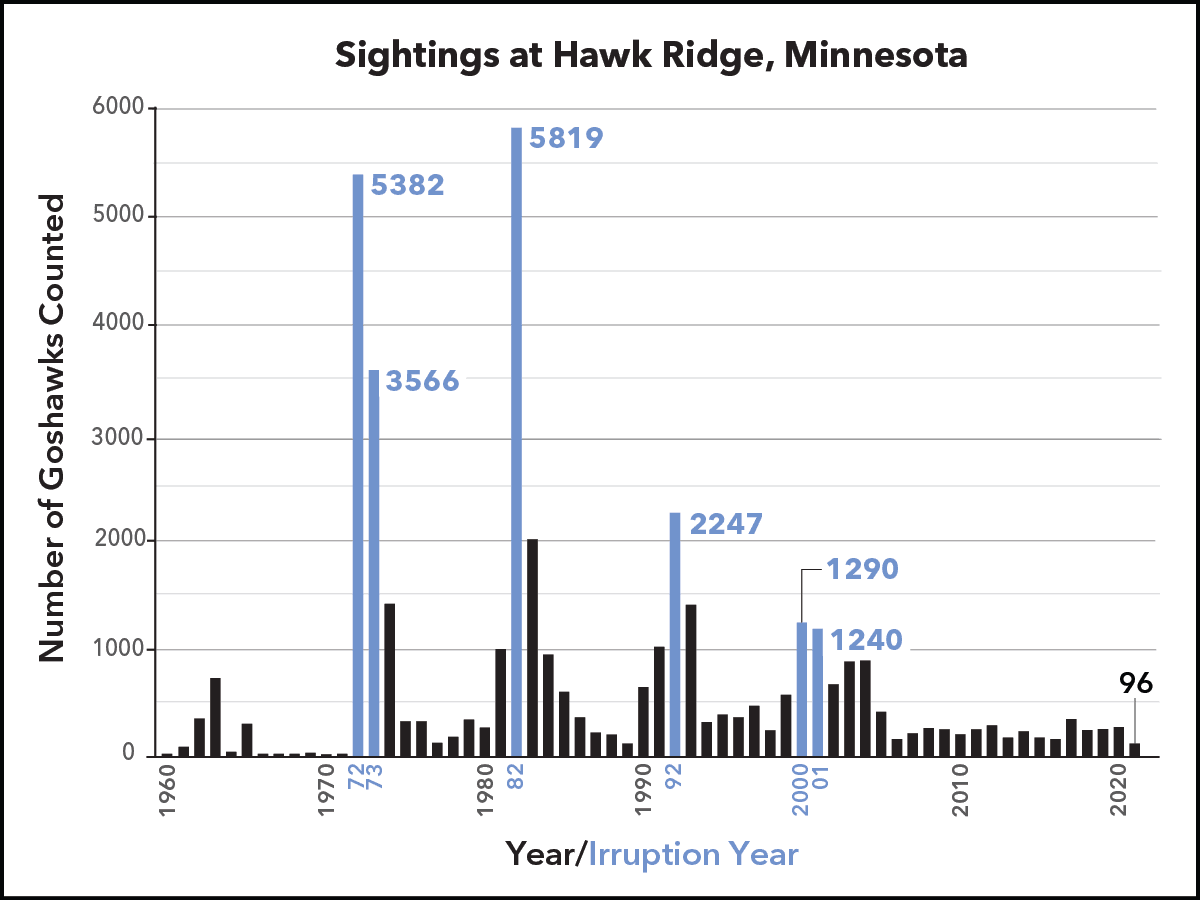

Goshawks are also famous for their sometimes cyclical invasion flights, especially in the western Great Lakes. These irruptions peaked in the 1970s and 80s, when close to 6,000 goshawks might pass a count site like Hawk Ridge in Duluth, Minnesota, in a single autumn. Yet many hawkwatchers fear such floods have faded away; last autumn, Hawk Ridge didn’t even break 100 goshawks. Some scientists look at dwindling goshawk migration counts and see the signature of climate change and habitat alteration. But other goshawk specialists caution that there may be cycles within cycles within cycles, and they are cautiously optimistic that the glory days of huge goshawk flights will return.

“Our Most Savage Destroyer of Small Game”

Growing up in eastern Pennsylvania in the 1970s, I knew goshawks as only a rare autumn and winter migrant, and that had been the case in the central Appalachian Mountains for at least a century before. Their breeding range lay well to the north. In the Northeast, goshawks were considered rare through most of the 20th century—in contrast to accounts from 19th-century ornithologists, who said that “partridge hawks” or “gray hawks,” as they were sometimes called, were once rather common, especially around the enormous Passenger Pigeon colonies that periodically settled to nest in the region. One naturalist was quoted as saying that “he always met with goshawks about the nesting places of the wild pigeons, but when the pigeons left his locality these hawks also departed, and are now seen there only as rare winter visitors.”

The all-but-complete cutting of the old-growth forests in the 18th and early 19th centuries also hastened the goshawk’s decline. Direct persecution undoubtedly played a role, too; goshawks were derided even by early ornithologists like George Miksch Sutton as “our most savage destroyer of small game.”

Raptor Conservation

All that changed, slowly, through the first two-thirds of the 20th century. As the forests of the Northeast and Upper Midwest regrew, goshawks slowly reclaimed some of their old realm. In 1980, not far from where I then lived in southeastern Pennsylvania, friends of mine found the first nesting pair of goshawks seen in that part of the state since, in all likelihood, the middle 1800s. A similar story was playing out in other parts of the central Appalachians. During Pennsylvania’s first breeding bird atlas in the 1980s, goshawks were reported from 34 of 67 counties, mostly in the northern half of the state. Farther south, nesting goshawks were reappearing in small numbers in the mountains of West Virginia, in the highlands of western Maryland, and in western Virginia, where many years of unconfirmed reports culminated with the first documented nest in 2012.

Paradoxically, even as nesting goshawks were recolonizing old haunts, their numbers seemed to be on a downward slide at many autumn migration count sites. According to the Raptor Population Index, a collaborative analysis of North American migration-count data, migrant goshawk numbers have remained fairly stable in the West. But there have been some declines in the western Great Lakes, and in the eastern Great Lakes and Appalachians migrant gos numbers have fallen sharply. For example, Waggoner’s Gap, a major hawk-count site in central Pennsylvania, has seen decreases of 15% per year for the last 10 years, according to Raptor Population Index data.

One reason for these seemingly contradictory trends may lie in some unusual aspects of goshawk migration. Taken as a whole, Northern Goshawks are what ornithologists call “partial migrants,” a species with a mix of resident and migratory individuals or populations. Many goshawks that nest across the West appear to be entirely resident, and the same goes for those in the Upper Midwest and East, where the goshawks seen at autumn migration-count sites are usually dispersing juveniles. Populations farther north, especially in the northern Canadian boreal zone from Manitoba to Alberta, also stay put— usually. Sometimes, though, circumstances in the forest take a turn for the worse, and when they do, the result is perhaps the most intriguing facet of this fascinating raptor: a goshawk “invasion.”

A Decadal Cycle in Decline

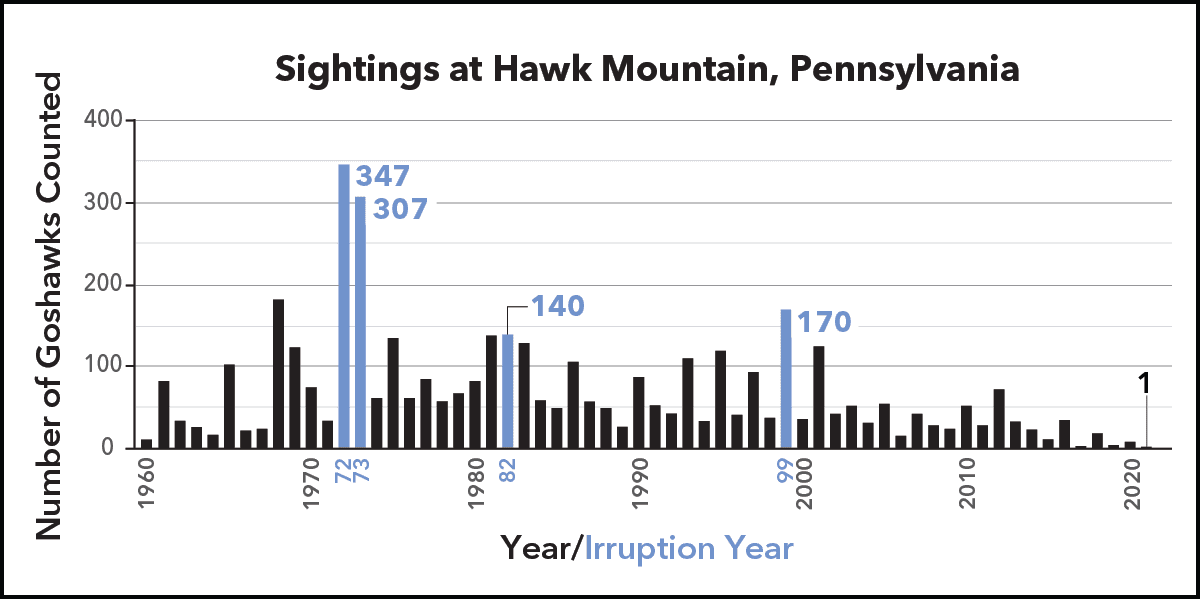

At least as far back as the 1890s, naturalists and ornithologists realized that at roughly 10-year intervals, larger-than-normal flights of goshawks move down from the north. Such irruptions can last a single season or stretch over two or more years. The irruptions can reach into the East; Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania tallied nearly 350 goshawks on a migration count in 1972. But the real epicenter for gos irruptions is the western Great Lakes, especially Hawk Ridge in Minnesota, which sits on a bluff high above Lake Superior. Avian migrants of all stripes coming south out of Canada encounter the immense lake’s northern shore, which turns and concentrates them south and west past Hawk Ridge. There was a huge two-year irruption in 1972 and 1973, with 5,382 goshawks in the first autumn and 3,566 goshawks counted the following year. A decade later, an exceptional irruption in 1982 brought 5,819 goshawks past the ridge, including a one-day high of 1,229 goshawks.

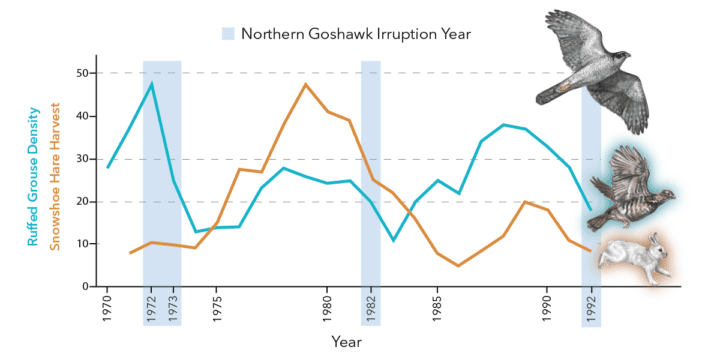

The roughly 10-year periodicity of these invasions is no coincidence. In the boreal forests of Canada and Alaska that comprise their core breeding range, a goshawk’s primary prey species—including Ruffed Grouse, and especially snowshoe hares—undergo dramatic, decadal population cycles. When hare and grouse numbers are ascendant, goshawks are able to breed successfully, rearing up to five chicks per clutch. In such boom years, ironically, migration counts in the northern U.S. tend to be much lower, and are dominated mostly by dispersing juveniles. But when the hare or grouse cycle collapses, and especially if both crash at the same time, large numbers of hungry, primarily adult goshawks are forced south—a classic winter irruption.

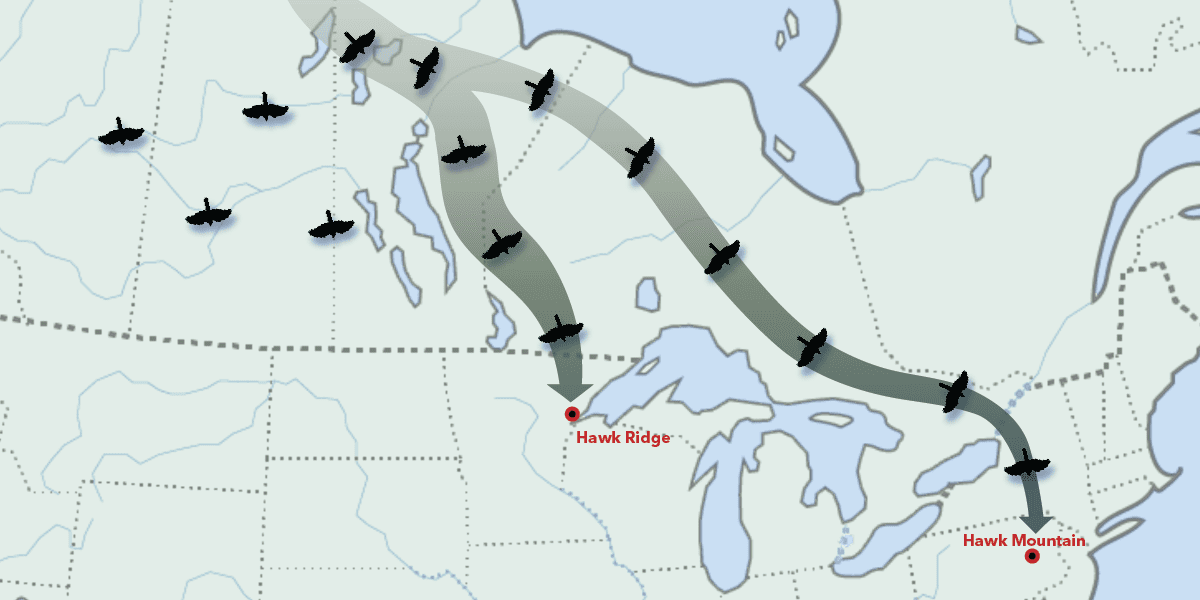

In a normal winter in the East and Midwest, goshawks rarely appear much farther south than the southern edge of the Great Lakes and the central Appalachians. In a big invasion year, however, they may range as far south as Texas and northern Mexico, the Gulf states, and even Bermuda. Band recoveries show that at least some of the goshawks in the Great Lakes irruptions come from as far away as Alberta and the Northwest Territories.

Frank Nicoletti and Dr. Richard Green have spent decades puzzling over the dynamics of goshawk invasions in Minnesota. Green is an emeritus professor of mathematics at the University of Minnesota Duluth, and a goshawk fanatic of long standing; Nicoletti is a raptor bander and researcher who left the East after working at bird observatories in New York and New Jersey and came to Hawk Ridge in 1991 specifically to watch, count, trap, and band goshawks. In a way, though, Nicoletti missed the real party. Except for a modest invasion in 1992–93 that was roughly a third the magnitude of the 1982 flight, and an even smaller pulse from 2000 to 2004, the big goshawk irruptions seem to have faded away. The 2021 goshawk count at Hawk Ridge, just 96 birds, was the lowest on record. The story has been even more stark at eastern count sites like Hawk Mountain, where there have been no large irruptions since 1972–73. In most recent years, the total goshawk count at Hawk Mountain has been in the low single digits; last fall it was just one gos.

More than a few goshawk aficionados fear something has gone fundamentally wrong with the cycles that once drove huge goshawk invasions. Perhaps climate change, or habitat fragmentation from clearcut logging in the Canadian boreal forest, or both are altering the dynamics of the hare and grouse cycles that underpin goshawk irruptions. In the past 15 years or so, scientists around the world have voiced concern that natural cycles of many sorts are slowing or vanishing.

Cycles Within Cycles

Not everyone is convinced, and skeptics of widespread cyclical collapses point to some “vanished” cycles, like those among voles in Finland, that reemerged some years later. Many of the experts I spoke to cautioned me about the particular difficulty in understanding the dynamics of cyclical systems with long intervals, like the 10-year hare and goshawk cycles. Half a century of study is a lifetime’s work for a scientist, but only five data points for a decadal cycle.

In Duluth, Green has tried to flesh out a more complete picture of goshawk fluctuations by piecing together all manner of old records—newspaper accounts, bounty payments, tallies of raptors killed a century or more ago to analyze their stomach contents, old taxidermists’ records—to sketch out the timing and extent of goshawk irruptions long before widespread migration counts were taking place. Those results, intriguingly, suggest cycles within cycles within cycles.

It appears there was a big invasion in the mid-1920s and another in 1935 observed at Hawk Mountain.

“But then basically in the 40s and 50s, there isn’t very much—I mean, you could argue there almost wasn’t anything,” Green said. “Then there was an invasion in the 60s, and again a lot more in the 70s. You can say we haven’t had a real invasion since the big one in the 80s, but you could also argue that from the 20s to the 70s there wasn’t much, either.”

Surveys from Wisconsin of two prime prey species for Northern Goshawks may hold a clue to the peak goshawk counts at Hawk Ridge and Hawk Mountain. A downward slide in the Ruffed Grouse and Snowshoe Hare population cycles appeared to coincide with the goshawk invasion years. If those same grouse/hare cycles were playing out in Canada, the drop-off in prey may have been a driving factor in goshawk invasions south into the U.S. Ruffed Grouse numbers are drums per survey transect; snowshoe hare numbers are x10,000. Source: Graph from Erdman, et al., Productivity, Population Trend, and Status of Northern Goshawks, Accipiter gentilis atricapillus, in Northeastern Wisconsin. Canadian Field-Naturalist. 1998; Data from Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and Hawk Ridge/Hawk Mountain raptor counts. Graphic by Elizabeth Wahid, Bartels Science Illustrator.

Green and Nicoletti are optimists, and they believe the current lull in big irruptions could be part of a long-term pattern that the data do not yet fully capture, much like the lull in the middle of the 20th century.

“I’m a firm believer that irruptions still will happen, though whether they’re going to be as big as the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, I don’t know. But [the irruptions] in the ’80s and ’90s and 2000s were quite good,” Nicoletti said.

Green also pointed out that in the absence of huge decadal swings, another pattern emerges from goshawk counts, one first detected in Hawk Mountain’s first 40 years of data—a four-year cycle, with two up years followed by two down years. Even at Hawk Ridge, ever since goshawk flights became much more modest starting in 2005, Green has seen this pattern surface. The explanation for it likely also lies in goshawk prey.

Hare, Grouse, Squirrel, or Crow for Dinner?

Dave Brinker got hooked on goshawks as a recent graduate from University of Wisconsin–Green Bay in the late 1970s. Weekdays, he was conducting fieldwork for an environmental consulting company at a proposed mine site in northern Wisconsin, but on his own time, he began helping Tom Erdman, then the curator of the university’s Richter Museum of Natural History. Erdman was studying forest raptors in the same area, and Brinker helped him find goshawk nests and band the chicks. After Brinker took a job as a wildlife biologist with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources in 1989, he realized he had a chance to compare what his mentor had learned about the accipiters over decades in the Great Lakes with the reemerging population in the mid-Atlantic region. So in his spare time, he started a multi-state goshawk study.

Brinker began his new project in 1990 in West Virginia, where a few goshawk nests had recently been discovered, and later expanded it to western Maryland where goshawks had likewise reappeared. He quickly found there were significant differences between the Wisconsin goshawks he knew and this central Appalachian population. For instance, all the nests he and Erdman had located in Wisconsin were in deciduous forest, usually mature stands of maple, beech, aspen, and birch.

“So it took a while to get used to the fact that here in the Appalachians, conifers are really important,” Brinker said. “We probably find more gos nests in maturing red and white pine stands, some of which were former plantations from the CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps] era.”

There was also a big difference in prey, Brinker said: “Up in Wisconsin they’re eating a lot of snowshoe hares, they’re eating a lot of grouse, some gray squirrels. Red squirrels were fairly frequent, but I don’t think we ever saw a chipmunk in a goshawk nest in Wisconsin.”

In the central Appalachians, though, the most important gos prey species are red squirrels, American Crows, Ruffed Grouse, and chipmunks—and in some years, chipmunks in remarkable numbers. In the 2020 nesting season, every goshawk nest Brinker checked had chipmunk remains. The four-year population cycles in red squirrels and chipmunks, Brinker thinks, account for that two-years-up, two-years-down pattern that is obvious in fall goshawk counts in the Great Lakes and East, when the signal isn’t overwhelmed by decadal irruptions.

Brinker started working with goshawks in Allegheny National Forest in 2001, drawn by reports that U.S. Forest Service biologists were regularly finding several dozen nesting pairs there. But as he would soon learn, the glory days were already passing. The late 1990s proved to be a high-water mark for the mid-Atlantic goshawk population. Brinker blames two factors that arrived in the 1990s for this more recent decline— a newly introduced pathogen, and (perhaps) a reintroduced mammal.

Vanishing Goshawk Nests

West Nile Virus, initially described from Africa in the 1930s and spread by mosquitoes, first appeared in North America in 1999, though by what means it arrived remains a mystery. It kills anywhere from a few dozen to a few hundred people a year. But it is also a serious avian disease, and has been detected in more than 250 species of wild North American birds, with especially high mortality rates for raptors, corvids, and some grouse.

In 2001 the USFS gave Dave Brinker the locations of about 20 recently active goshawk territories in the Allegheny National Forest, and he hit the woods to find them.

Two of the most important prey species for goshawks are crows and grouse, both of which have proven to be very susceptible to the virus.

“But a lot of them ended up being vacant,” he said. It was baffling. “The nests were still up in the trees, but a lot of these territories didn’t have birds in them.”

From that frustrating beginning, the population built itself back up, and in a good year in the early 2010s Brinker and his goshawk team, composed of Forest Service staff and a number of local birders, might find a dozen or more nests in the Allegheny National Forest. But then the numbers started to slide again.

“Back then, we had no clue what the problem might be,” Brinker said. It took a while before the connection with the sudden goshawk decline and West Nile began to suggest itself.

Brinker and others now think West Nile Virus has multiple impacts on goshawks. There is the direct loss from illness, which varies year to year depending on mosquito populations. He, Erdman in Wisconsin, and a colleague in New York have been taking blood samples from goshawk adults and nestlings; about 60% of all the adults show signs of previous infection, sometimes repeatedly. And by the time the chicks fledge in midsummer, the risk of WNV exposure is nearing its seasonal peak. Brinker suspects many of the youngsters simply don’t survive their first bout of the illness. Furthermore, two of the most important prey species for goshawks in the central Appalachians are crows and grouse, both of which have themselves proven to be very susceptible to the virus. Ruffed Grouse populations in Pennsylvania have been in a decades-long slump, and biologists believe West Nile is at least partly to blame.

More controversially, Brinker believes the central Appalachian goshawks are facing another challenge, one that he and his mentor Tom Erdman, now retired from the Richter Museum, also saw play out in Wisconsin—fishers, a natural predator of gos nests. Fishers are fox-sized weasels that can climb trees with ease, and although they had been extirpated from the Great Lakes, they were reintroduced to Wisconsin in the 1950s and 60s. Erdman is convinced fisher predation is the reason that goshawks, which had recolonized central and even parts of southern Wisconsin by the 1980s, later underwent a significant range contraction back to the north, even before West Nile Virus arrived.

“In the late 80s, fishers just exploded” in Wisconsin, Erdman told me, their numbers supported through bad winter weather by scavenging from Wisconsin’s burgeoning deer herd. In Door County north of Green Bay, where he once had half a dozen or more active goshawk territories, Erdman said he knows of none today. The few successful gos nests he still monitors elsewhere in Wisconsin are all protected by no-climb metal predator guards on the tree trunks.

In Pennsylvania—where fishers were reintroduced in the mid-1990s, to supplement natural dispersal from West Virginia and New York—Brinker has video camera-trap footage of fishers taking goshawk chicks from nests. He has also found evidence to suggest the carnivores kill incubating adult females at night.

Not everyone is convinced that fishers are a problem for goshawks, though—or at least, maybe not the main problem. Dr. Laurie Goodrich is the director of conservation science at Hawk Mountain, and a member (along with Brinker) of an effort by the nongovernmental Pennsylvania Biological Survey to learn more about the declining goshawk population.

“I haven’t been persuaded that [fishers] are the one thing that’s causing goshawks to decline,” Goodrich said. “I feel [fishers] were a natural part of the community for a long time, so there should be some kind of adaptation to that level of predation or predator activity.”

Sean Murphy, state ornithologist with the Pennsylvania Game Commission, also said the two would have coexisted in the past, but added that the agency’s furbearer experts have told him fisher populations in the state today probably surpass historical densities.

In fairness, Dave Brinker also told me that he believes goshawks likely could handle fisher predation, if that were the only big pressure on them.

“But when you combine fishers taking adult females off nests, and also taking a fair number of chicks out of nests, and then you add West Nile, the synergism between the two certainly seems to be enough to push the kind of decline that we’re seeing in the Northeast,” he said. Brinker notes that breeding bird atlases from the mid-Atlantic to New England and Ontario have shown declines of up to 40% in nesting goshawks.

Contentious Legal Battles Over Forest Management

In 2021—a year when only two active goshawk nests could be located anywhere in Pennsylvania—the state Game Commission listed Northern Goshawk as an endangered species, and barred the already very limited take of gos chicks for falconry. The state listing proposal drew relatively little criticism outside some grumbling from the falconry community, Murphy said. But in other parts of North America, goshawk management has been a lightning rod because of the bird’s association with old-growth Western forests.

Goshawks have been at the center of contentious legal battles over forest management in parts of the West and Southwest, where in the 1990s and early 2000s conservation groups battled the U.S. Forest Service to protect mature and old-growth stands on national forest lands where goshawks occurred. The groups sued the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to force it to list southwestern populations of the Northern Goshawk as federally Endangered. While the ESA petitions failed, many national forests from Alaska and California to Arizona and New Mexico have instituted management plans designed to take into account the large areas of mature forest that goshawks are believed to require.

The one thing a goshawk needs is the structure of a natural forest ecosystem in all its pieces.

Wildlife biologist Frank I. Doyle

To Frank I. Doyle, the need to preserve big chunks of mature forest habitat for goshawks is a settled question, but one with profound implications in places where timber propels the economy. Doyle is a registered wildlife biologist in British Columbia who has been studying goshawks in western Canada, in both heavily logged forests and relatively pristine ecosystems, for nearly 35 years.

Goshawks need a lot of land. In the Allegheny National Forest, Dave Brinker’s tagged goshawks use about 2,500 to 4,800 hectares (9.7 to 18.8 square miles) for nesting, and up to 17,000 hectares (66 square miles) in winter. Doyle’s research shows that goshawk breeding territories in mainland British Columbia are even larger, averaging 4,000 to 6,000 hectares (roughly 15 to 23 square miles). The industrial scale of logging in western Canada, with enormous clearcuts that are reforested with dense plantations of young trees, ruins the landscape for the big accipiters, Doyle believes. More than two-thirds of the time, he said, goshawks will abandon a territory if just 20% of it is clearcut; once 25% or 30% of it is cut, the abandonment rate is total. In the heavily timbered areas he’s studied in southern British Columbia, fewer than 10% of the goshawk territories that he mapped in the 1990s are still active.

“We don’t need more science, we need action,” Doyle said, meaning changes to how forests are harvested. In his view, goshawks are actually remarkably adaptable, taking a wide variety of prey species, and using many kinds of habitat within the natural mosaic of boreal forest, from thick woods to grassy openings.

“But the one thing a goshawk needs is the structure of a natural forest ecosystem in all its pieces,” Doyle said. The naked expanse of a clearcut is useless to a goshawk, as are the immense, unnatural thickets of planted seedlings that grow up in its wake, which don’t allow the hawks to see and chase their prey.

The solution, Doyle thinks, is to harvest trees in ways that re-create the complexity of natural forests, with smaller cuts that create more naturalistic openings; with snags (dead trees) left standing and coarse woody debris left on the forest floor; and with plans to create a range of tree age classes, including uncut, mature stands. That requires a major shift in forest management. But Doyle sounds optimistic, even as he sits on a team that drafted a 2018 Canadian recovery strategy for the coastal subspecies of goshawks in British Columbia, which is listed as federally Threatened.

“I know we will be successful in a number of areas, and that’s just because of the goodwill and the impetus that has gotten the ball rolling. Government is certainly on our side, the [logging] licensees are on our side. So I think we’ll have some success, but whether we’ll have enough success to maintain a population …” Doyle let the thought trail off.

Doyle points to the archipelago of Haida Gwaii off the coast of British Columbia as an example of a societal sense of wanting to do right by goshawks. There, logging of temperate rain forest and other pressures have pared the islands’ population of darkly plumaged, genetically distinct goshawks to fewer than 100 birds. In response, the Indigenous Haida Nation has created a dozen goshawk reserve zones to protect nesting and foraging areas.

“There’s great impetus culturally, across the board from industry and from government and the general public, to try and get it right on Haida Gwaii,” Doyle said.

Logging, exotic disease, hungry carnivores, a changing climate; it’s a lot for even a superb predator like a goshawk to surmount. Yet the optimism I heard from some of this great raptor’s most ardent admirers buoyed me.

Dave Brinker jokingly suggested to me that geneticists should tweak the goshawk’s DNA to make them resistant to West Nile Virus. But all kidding aside, scientists have shown that some species, like House Sparrows, are evolving resistance to the disease on their own. It’s possible, perhaps even likely, that with time Northern Goshawks will adapt to this new pathogen.

I hope so. And if Frank Nicoletti and Richard Green are right, and we’re just in a long, natural lull between mega-invasions—well, I hope I’ve earned enough raptorial karma to be around the next time a gray flood comes down from the north, and partridge hawks rule the skies again.

Scott Weidensaul is a migration researcher and the author, most recently, of the New York Times bestseller A World on the Wing. As a disclaimer, he notes that his personal and professional lives have intersected with a number of people with whom he discussed goshawks for this article. He says Dave Brinker is an old friend and colleague on projects involving Northern Saw-whet and Snowy Owls, as well as the Motus Wildlife Tracking System. He notes that Frank Nicoletti, Laurie Goodrich, and Sean Murphy at the Pennsylvania Game Commission are also variously friends, acquaintances, or colleagues. The world of raptor research, Weidensaul says, is a rather small one.

Duluth, Minnesota–based photographer Dudley Edmondson has had his work featured in numerous books, magazines, and galleries around the world. He recently appeared in an episode of the PBS series America Outdoors, in which he took host Baratunde Thurston birding at Hawk Ridge.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library